Part 1

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth.

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth.

The "Gran Aldea" (Great Village) became a cosmopolitan city, which, despite its isolated geographic location, was one of the greatest cities in the world.

During this period of multiethnic and multicultural interaction, Tango developed its unique characteristics and became a cultural identity, philosophy of life, and lifestyle. Its name was not mentioned in well-mannered conversations. It was practiced, protected, and cared for by powerful people, the only ones who would not care about its bad reputation and defy the rejection by the comfortable, afraid, and obedient society. It needed to develop in places prohibited by a society that denied that an entirely new creature was coming to life. A creature not a child of a well-established family, in the portrait of religions and hypocritical political speeches. A being that was happily excited to deal with the chaos of unpredictability, with all that can't be rationalized, accounted for, and fit in the big plan laid out by the ruling classes for the population of that corner of the world.

Even when Tango began to enter family homes and broadly accepted social events, the name Tango would not be used as the label to refer to it, nor would the musicians use this term to describe the orchestras.

The dance technique that today we associate with Tango and milonga, the "cortes and quebradas", was in its origins a dance technique created by the "chinas" and "compadritos" and applied to all kinds of danceable music played in Rio de La Plata: "mazurka", "polka", "habanera", "cuadrilla", "lanceros", waltz (called "vals cruzado" when danced in this way), "pasodoble", "Spanish tango", Tango and milonga.

Later this dancing technique remained in Argentine Tango (referred to as "tango criollo"), milonga, and vals criollo because these music styles were better suited to it.

On September 9, 1862, four men and two women were put in jail for dancing “tirando cortes y quebradas” at a conventillo of Paraguay 58 (today, in Puerto Madero).

The police report does not mention Tango or milonga.

It was on September 28, 1897, that for the first time we find that the “cortes and quebradas” are elements associated to the choreography of a particular music called Tango. It is at the play written by Ezequiel Soria “Justicia Criolla”:

“Era un domingo de carnaval

Y al “Pasatiempo” fuime a bailar.

Hablé a la Juana para un chats

Y a enamorarla me decidí.

En sus oídos me lamenté

Me puse tierno y tanto hablé,

Que la muchacha se conmovió

Con mil promesas de eterno amor.

Hablé a la mina de mi valor

Y que soy hombre de largo spor,

Cuando el estrilo quiera agarrar

Vos, mi Juanita, me has de calmar.

Y ella callaba y entonces yo

Hice prodigios de ilustración,

Luego, en un tango, che, me pasé

Y a puro corte la conquisté.”

And also:

“Qué cosa más rica...! Cuando bailando un tango con ella, me la afirmo en la cadera y me dejo ir al compás de la música y yo me hundo en sus ojos negros y ella dobla en mi pecho su cabeza y al dar vuelta, viene la quebradita... Ay! hermano se me vá, se me vá... el mal humor.”

The following year, in 1898, "El entrerriano", the first Argentine Tango registered by a known author, was published. This was the time before recordings when the music was commercialized by publishing it in music sheets. The author, Rosendo Mendizábal, was an Afro-Argentinean born in 1868 (and died in 1913). Coming from a wealthy family, he was able to study piano. Unfortunately, his lifestyle made him squander his fortune, and so he began to teach piano lessons and to play in all kinds of brothels and dancing houses, from the ones of the poorest clientele to those visited by the wealthiest people, like "Lo de Laura (Monserrat)" in Paraguay street 2512, where he premiered "El entrerriano", and dedicated it to Ricardo Segovia, a landowner born in the Argentine province of Entre Rios, who gave Rosendo a $100 bill. This was a common practice among composers before the benefits of authors' rights.

The following year, in 1898, "El entrerriano", the first Argentine Tango registered by a known author, was published. This was the time before recordings when the music was commercialized by publishing it in music sheets. The author, Rosendo Mendizábal, was an Afro-Argentinean born in 1868 (and died in 1913). Coming from a wealthy family, he was able to study piano. Unfortunately, his lifestyle made him squander his fortune, and so he began to teach piano lessons and to play in all kinds of brothels and dancing houses, from the ones of the poorest clientele to those visited by the wealthiest people, like "Lo de Laura (Monserrat)" in Paraguay street 2512, where he premiered "El entrerriano", and dedicated it to Ricardo Segovia, a landowner born in the Argentine province of Entre Rios, who gave Rosendo a $100 bill. This was a common practice among composers before the benefits of authors' rights.

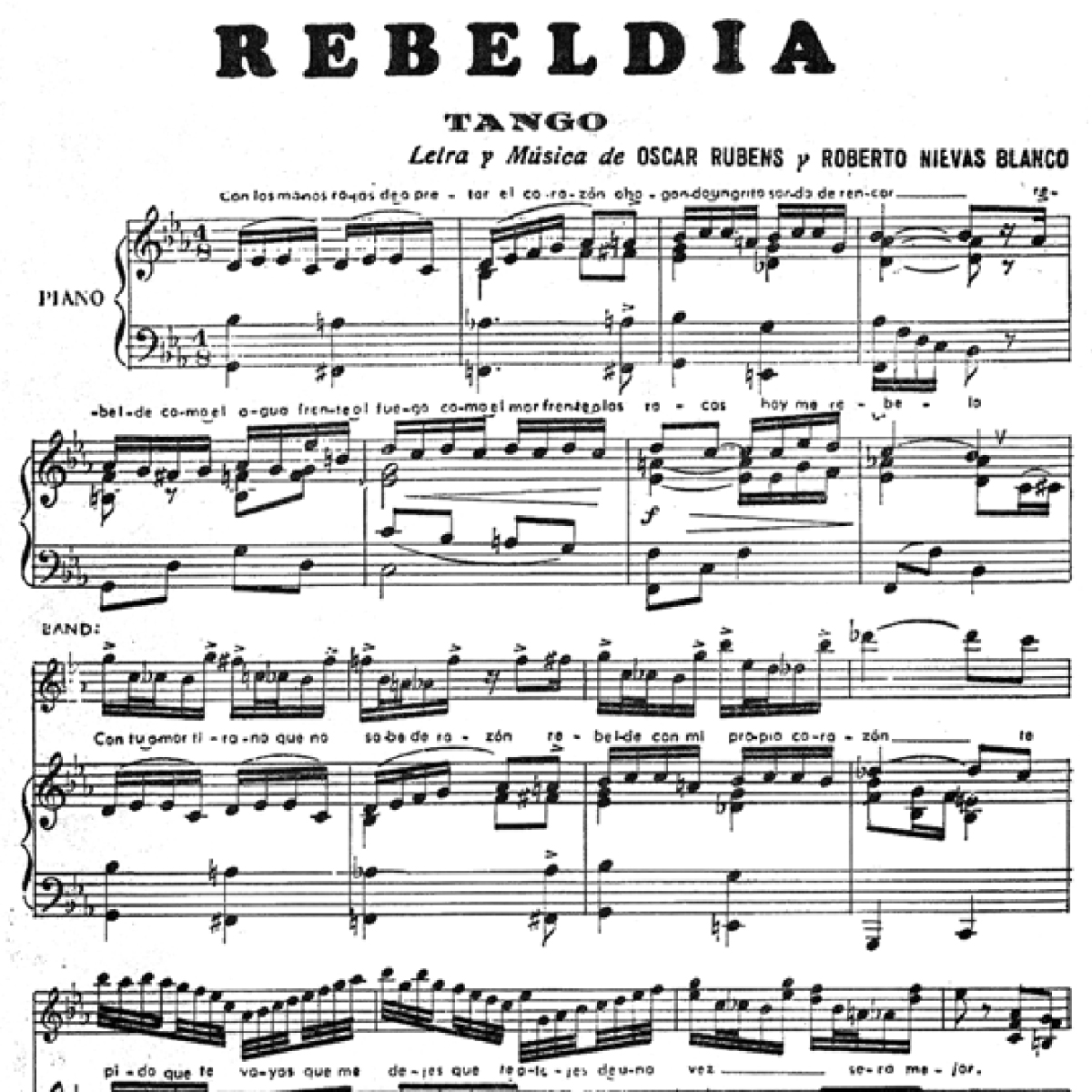

Before the publication of tangos, they became known only from the authors playing them over and over again in many places. When a tango was fortunate enough to be accepted by the audience, it was frequently requested, contributing to the recognition of the piece and its creator. Sometimes another musician would like a song and learn it by listening to it and incorporating it into his repertoire. But since the time that it began to be written, it was easier to propagate it. Eventually, musicians could play more and more varied songs, and city-sponsored orchestras, military and police bands, and club orchestras would be able to play them, contributing to a more excellent and more efficient divulgation of Tango. It was also how it could surreptitiously enter the family homes, hidden between piano methods and Chopin's waltzes. And, it made possible the printed rolls for "organitos", which played a significant role in the initial spread of Tango. Finally, it prepared the ears of those who initially liked Tango to accept a new instrument that became central to Tango and transformed it: the bandoneon.

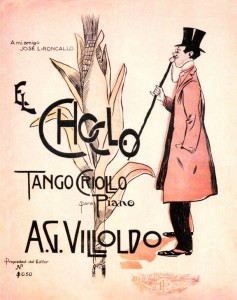

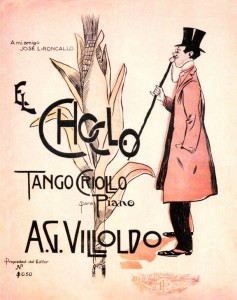

Enrique Santos Discépolo's father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote "El Choclo" to be played through this media) were involved in the construction of the first locally made cylinders for organitos.

Enrique Santos Discépolo's father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote "El Choclo" to be played through this media) were involved in the construction of the first locally made cylinders for organitos.

Related to this need for mobility that the primitive Tango required to spread itself and survive was the portability of the instruments of its origins. The guitar was the "criollo" (autochthonous) instrument par excellence, which the payadores chose to accompany their singing. It is, indeed, a privileged instrument to accompany the human voice. Still, the payadores that were already laureates and socially accepted, wouldn't, in general, risk losing their contracts playing such dubious music. The violin was also a prevalent instrument. Wind instruments rose in popularity to the extent that they showed up increasingly in bands and theatre orchestras of the time. The harmonica also played a decisive role, especially in the hands of Ángel Villoldo.

These instruments that first played Tango made their music energetic, lively, and shaky because they were high-pitch and light instruments that could easily be played fast. Later, with the introduction of the "bordoneos" (melodies and bridges played in the lowest pitch range of the guitar strings), the incorporation of the concertina and the Italian accordion, it will start a process of slowing down that will reach its depth with the bandoneon and the lower pitch string instruments. During this period, the bandoneon became the most characteristic instrument of Tango.

In 1899, "El Pibe" Ernesto Ponzio (1885-1934) published "Don Juan". "El Pibe" Ponzio played the violin "sacando chispas" (extracting sparks from it), according to the testimony left to us by Gabino Ezeiza. When his father (also a musician) died, he needed to help his family and went to play in canteens, at dance parties, and on the streetcars. Soon he was asked to play at the most famous places of the time, like "Lo de Hansen", "Lo de Laura", "Lo de María La Vasca" and "Lo de Mamita" Lavalle 2177, among many others. At this last one, it is said, he premiered "Don Juan", dedicating it to Juan Cabello, a well-known "compadre del arrabal" porteño. This tango was the first one recorded with bandoneon by Vicente Greco and his orchestra in 1910.

In 1924, when playing in Rosario, he shot and killed a man and was condemned to 20 years in prison. He had other previous violent incidents on his record, but he was pardoned in 1928 and returned to playing. According to his wife, he was not a violent person. He was handsome, kind, and always smiling, even when playing. Still, his talent, overwhelming energy, and charm as a musician, dancer, artist, and person provoked the envy and jealousy of those for whom beauty did not regard respect and tried to impose their mediocrity with sheer force. "El Pibe" Ernesto considered a lack of honesty with himself, with those he loved, and with his art, to retreat when insulted by disrespectful attitudes to people and what is beautiful in life. Nevertheless, he stood up for his thoughts and ideals in every moment, even difficult ones, and dealt with the consequences.

The only recording by "El Pibe" Ernesto Ponzio is in this scene from the first sound film made in Argentina, "Tango!" of 1933, playing his most celebrated composition:

In 1899 they closed the last "Academias" that remained in Montevideo, while the tango came to wider audiences entering the theater, tents, circuses, dance halls, and cabarets. Following this development, the original "tango canyengue" was transformed and made more "decent", smoothing or eliminating the "cortes y quebradas" and the most straightforward sexual elements of its practice, giving birth to the tango "salon", also known as tango "de pista" or 'liso".

Most of the precursors of tango music were also well recognized as great dancers.

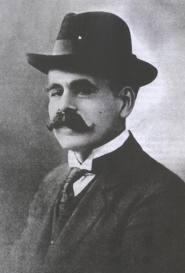

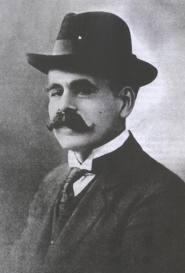

Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many "El padre del Tango" (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper "La Razón" in 1917, we know that he was "cuarteador" of "La Calle Larga" (The Long Street, today's Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many "El padre del Tango" (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper "La Razón" in 1917, we know that he was "cuarteador" of "La Calle Larga" (The Long Street, today's Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

Between 1879 and 1886, he was a typographer at the newspaper "La Nación" and Jacobo Peuser's print, conductor of the carnival choir "Los Nenes de Mamá Viuda", librettist for choir societies, a herdsman in two slaughterhouses of Buenos Aires, a clown at "Raffeto" circus.

Around 1900 he began to be known as a payador, composer, and singer in "Corrales Viejos" (Parque Patricios), Barracas, La Boca, Constitución, San Telmo, Palermo, and in Recoleta for the celebrations of the Virgen María in September. At these celebrations, big tents were erected for several days. They started to be frequented by "compadres" and "cuchilleros" , so their original character was replaced by another, less family-oriented, alcohol, dancing, and knife fighting. At these gatherings, in which the life of a man was of little value, everyone respected Ángel Villoldo, who performed there his first tangos.

The tango was still developing and had not yet achieved a defining shape. Therefore, the first works of Villoldo were milongas of the payador style that described characters and current events of the places he frequented. These first songs are precious testimonies of these times and their people. Like this milonga that refers to the known rivalry between cart drivers (carreros) and streetcars drivers (cocheros):

The tango was still developing and had not yet achieved a defining shape. Therefore, the first works of Villoldo were milongas of the payador style that described characters and current events of the places he frequented. These first songs are precious testimonies of these times and their people. Like this milonga that refers to the known rivalry between cart drivers (carreros) and streetcars drivers (cocheros):

"El Carrero y el Cochero", listen...

Villoldo's lyrics are "cheerful, wittily talkative, sometimes in jest, but never bawdy. The compadres of his stories are reliable criollos, as its creator, who recently left the horse on the outskirts of the city, men in whom the knife is not yet ostentatious bravado, but the defense of honor and cause" .

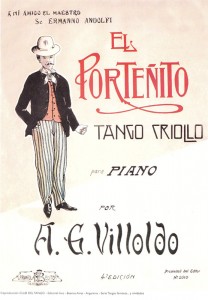

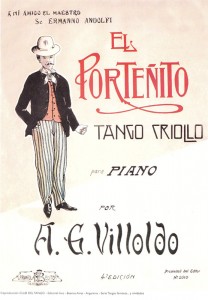

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang "El Porteñito" in the varieté Parisiana of Esmeralda Street, obtaining great success. Pepita Avellaneda had already sung several of his compositions a year earlier on Avenida de Mayo. Soon other female singers included his songs in their repertoire. In the same year, 1903, José Luis Roncallo premiered "El Choclo" at the restaurant "El Americano", labeling it as "danza criolla" since the category of the place did not admit including tangos in the playlist. After the truth was known, the audience demanded it is played every night. However, it was not published until 1905.

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang "El Porteñito" in the varieté Parisiana of Esmeralda Street, obtaining great success. Pepita Avellaneda had already sung several of his compositions a year earlier on Avenida de Mayo. Soon other female singers included his songs in their repertoire. In the same year, 1903, José Luis Roncallo premiered "El Choclo" at the restaurant "El Americano", labeling it as "danza criolla" since the category of the place did not admit including tangos in the playlist. After the truth was known, the audience demanded it is played every night. However, it was not published until 1905.

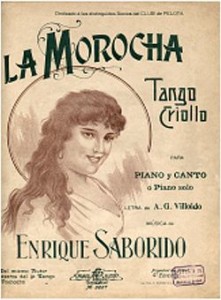

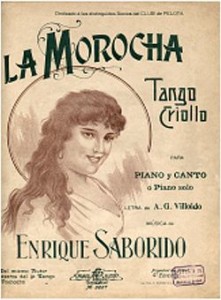

On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola "La Morocha", which she premiered that night. This tango was of great success, not only in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Argentina, and Uruguay, but copies of the music sheet were taken to many port cities worldwide by the school ship Fragata Sarmiento.

On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola "La Morocha", which she premiered that night. This tango was of great success, not only in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Argentina, and Uruguay, but copies of the music sheet were taken to many port cities worldwide by the school ship Fragata Sarmiento.

Villoldo finds humor in daily life events. In 1906 the Police Chief of Buenos Aires ordered a fine of 50 pesos to those who say "piropos" (compliments) to a woman in the street, and Villoldo composes, "Cuidao con los 50!". He tries to get extra advertisement for his song, so he goes to the street and starts to "piropear" to every woman he sees, expecting to be denounced and fined, making his song a way of protest, but all he got was a sweet "viejo enamorado" reply from one lady.

Around those years, "El esquinazo", another of his compositions, was prohibited from being played at "Lo de Hansen" because the crowd beat their glasses on their tables accompanying the song, breaking them, and making it too expensive for the business.

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with Alfredo Eusebio and Flora Gobbi (the parents of the great orchestra conductor Alfredo Gobbi). The recordings of Villoldo songs, already thriving, potentialize their success.

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with Alfredo Eusebio and Flora Gobbi (the parents of the great orchestra conductor Alfredo Gobbi). The recordings of Villoldo songs, already thriving, potentialize their success.

Edison invented the phonograph in 1877. Unfortunately, the sound quality on the phonograph was terrible, and each recording lasted for only one play. Alexander Graham Bell's graphophone followed Edison's phonograph. It could be played many times. However, each cylinder had to be recorded separately, making the same music's mass reproduction impossible with the graphophone.

On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The "arm" of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner's disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The "arm" of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner's disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

These inventions were taking place when tango was becoming more and more popular and are vital to the history of Tango.

Being in Paris, Villoldo subscribed to the Authors and Composers Association of France, following which then created in Buenos Aires in 1908 "La Sociedad del Pequeño Derecho", precursor of "SADAIC", created by, among others, Francisco Canaro, Osvaldo Fresedo, Augusto Berto, Agustín Bardi, Enrique Santos Discépolo and Francisco García Jiménez. This institution and its precedent, "Círculo Argentino de Autores Compositores de Música" and "Asociación de Autores y Compositores de Música", played an essential role in the history of tango and its existence since, thank them, the authors, composers, and musicians of tango were able to make a living.

https://escuelatangoba.com/marcelosolis/history-of-tango-part-3/

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth.

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth. The following year, in 1898,

The following year, in 1898,  Enrique Santos Discépolo's father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote

Enrique Santos Discépolo's father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote  Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many "El padre del Tango" (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper "La Razón" in 1917, we know that he was "cuarteador" of "La Calle Larga" (The Long Street, today's Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many "El padre del Tango" (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper "La Razón" in 1917, we know that he was "cuarteador" of "La Calle Larga" (The Long Street, today's Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang  On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola

On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with  On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The "arm" of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner's disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The "arm" of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner's disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.