In 1909, when Eduardo Arolas composed “Una noche de garufa”, he had not yet acquired a formalized musical education.

He was 17 years old.

Still, in his first composition, all the elements of his style are present, bursting out into the world for the amusement of those who, like us, love Tango.

This quality cannot be attributed to any other Tango composer.

None of his colleagues had a defined style during their first compositions and would need many years to develop it. Arolas’ works have such advanced characteristics that they will keep forever surprising Tango lovers wondering how what inspiration and from which source Arolas extracted them.

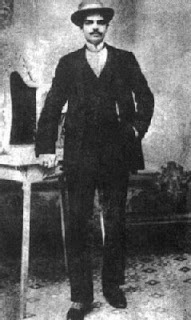

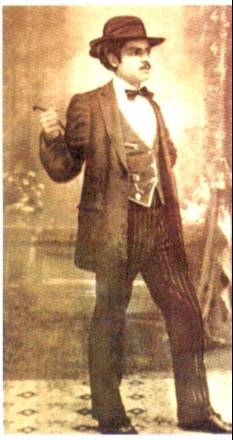

He was born on February 24, 1892, in the nascent industrial neighborhood of Barracas, on the southern edge of Buenos Aires, where he grew up playing among workshops, construction sites, warehouses, deposits, workers, cart drivers, cuarteadores, payadores, and herdsmen.

At six years old, he started learning to play the guitar from his brother José Enrique.

Until 1906 he played this instrument with friends in informal settings and eventually began playing gigs at Cafés and Dancings in his neighborhood. Arolas was regarded as a skillful and versatile player.

He accompanied Ricardo González “Muchila”, who played the bandoneon. The sound of this instrument exerted a strong attraction on Arolas. He acquired a small one with 32 notes and began learning from Muchila.

After selling merchandise on the streets for many years, his parents opened a wholesale store and bar in front of the train station. Arolas, known as “el Pibe Eduardo”, and his brother played Waldteufel waltzes to entertain the clientele, which was very in vogue then.

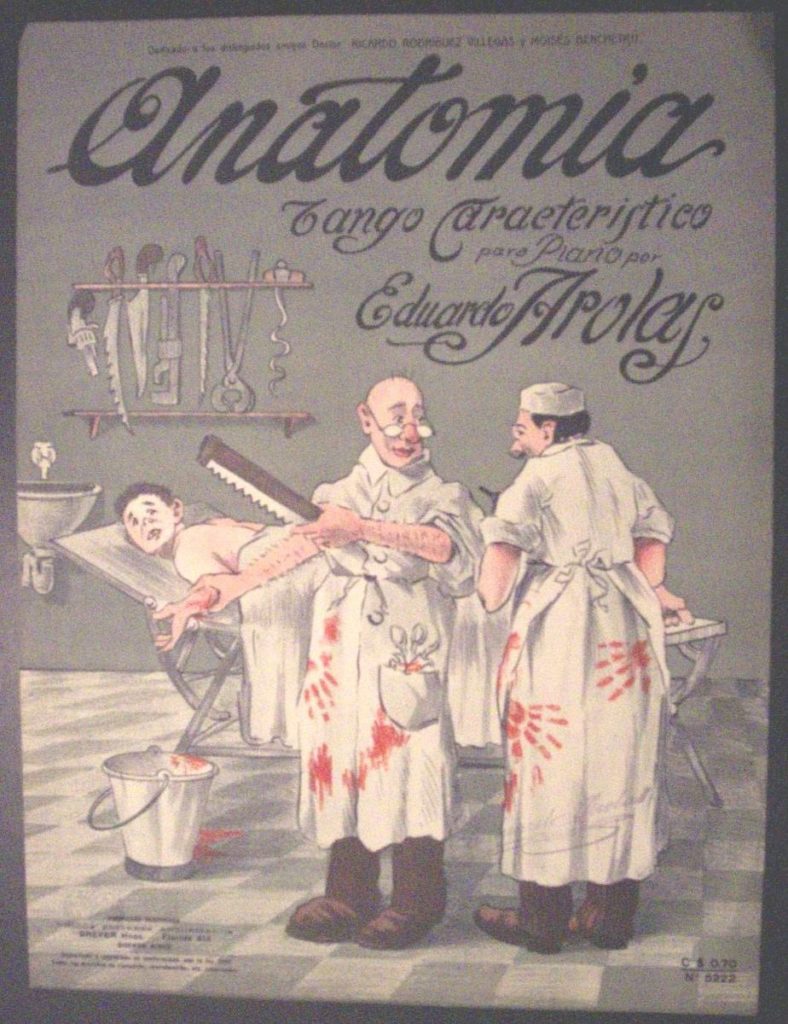

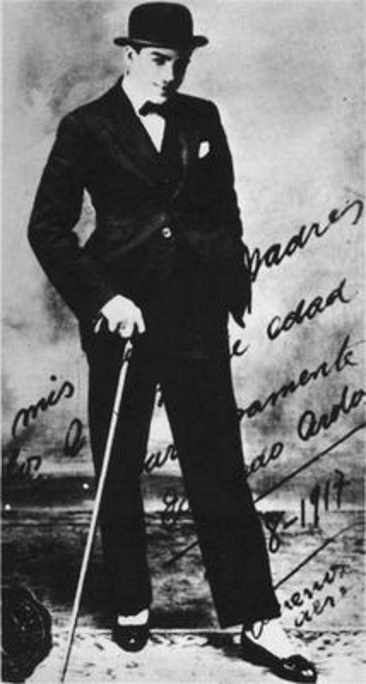

After finishing third grade, he quit school. He began working different jobs to help his family: busboy, delivery boy, apprentice at a print workshop, manufacturing of commercial signs, illustrator, decorator, and cartoonist, which became another of his passions, as seen in the drawings and artwork covers of his own published music compositions and for some colleagues.

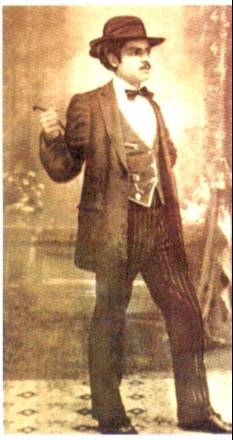

On the record sheet of his neighborhood police station, he appeared classified as “compadrito”.

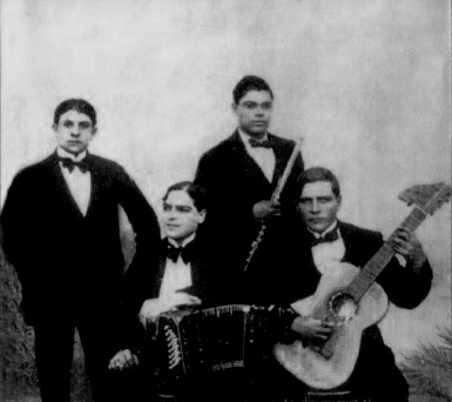

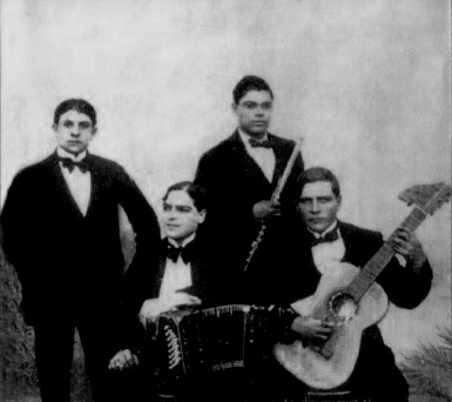

In 1909 he played a 42-button bandoneon, accompanied by Graciano De Leone on guitar.

That same year he presented his first composition to

Francisco Canaro.

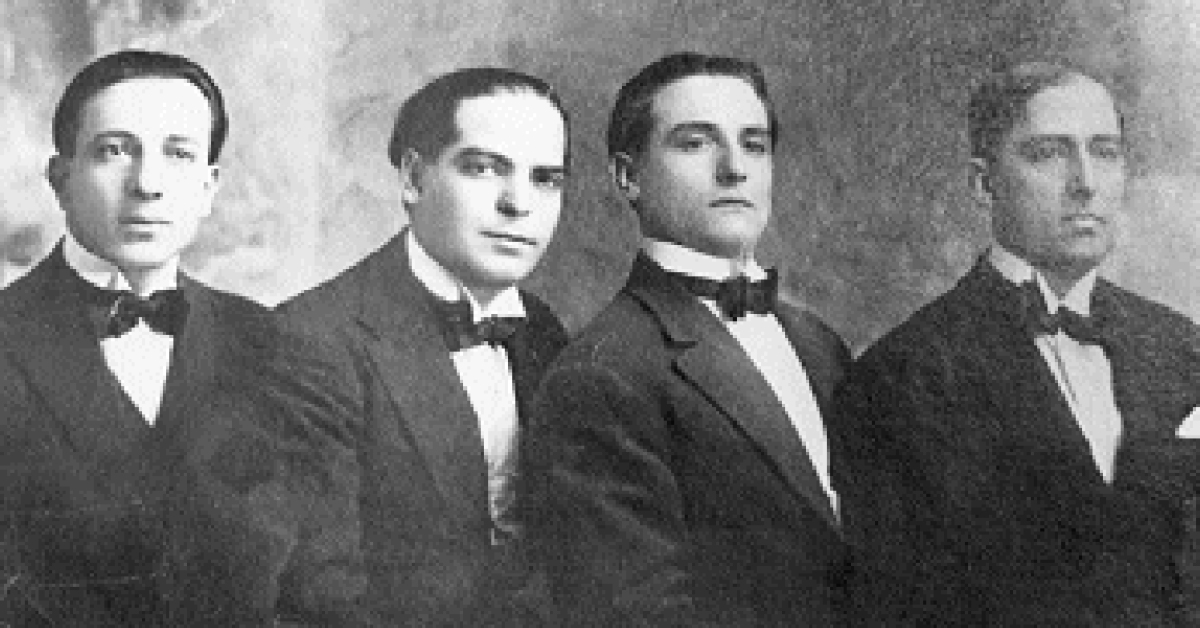

In 1910 he played with Tito Roccatagliatta, the most important violin player of that era; Leopoldo Thomson, who established the double bass in the orquestas típicas; and Prudencio Aragón, pianist and composer, author of “Siete palabras”.

In 1911, at 19 years old, he played in Montevideo for the first time, which would become his home when broken-hearted, he exiled himself voluntarily from Buenos Aires. At this gig, Arolas played a bandoneon of standard 71 buttons.

Upon his return from this trip, he started formal musical studies with José Bombig, conductor of the National Penitentiary band, who had a conservatory on Avenue Almirante Brown in La Boca neighborhood.

During those three years at the conservatory, he made an extensive and profitable tour of the province's brothels with violinists Ernesto Zambonini and Rafael Tuegols.

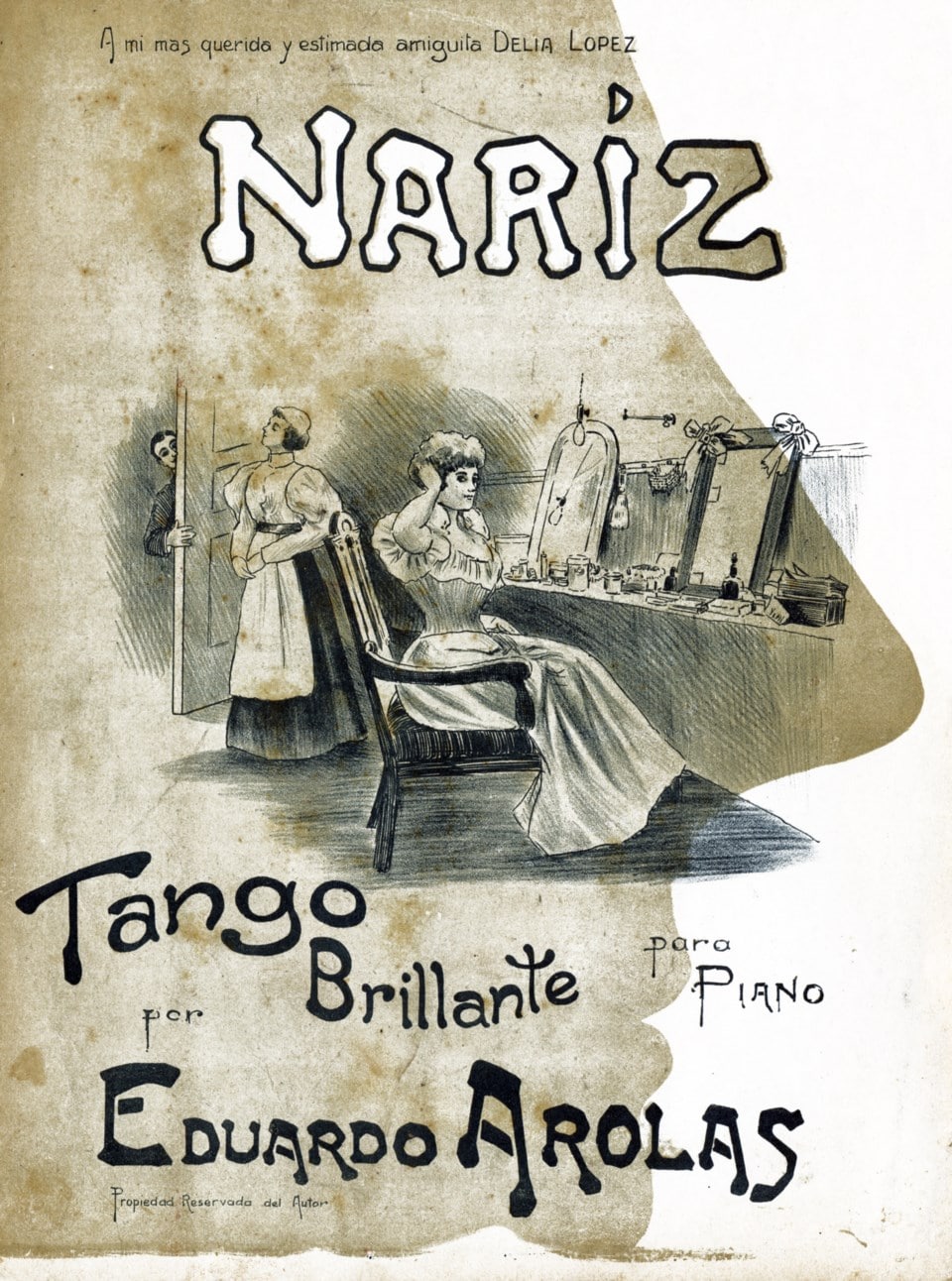

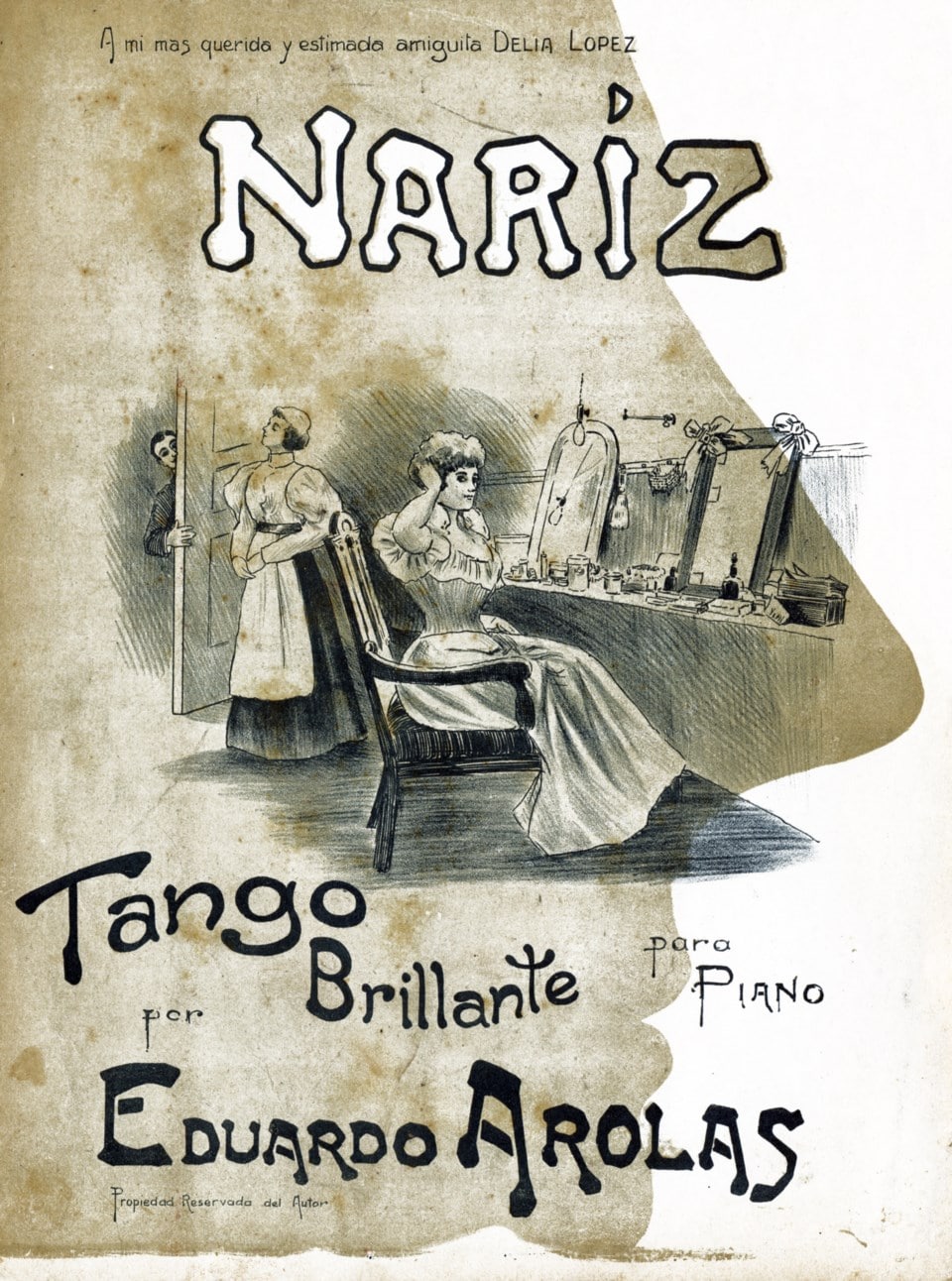

While on this tour, he met Delia López, “La Chiquita”, and started a relationship that became a source of great inspiration for him and the likely trigger of the unfortunate choices that accelerated his demise.

Back in Buenos Aires, he mainly worked in his neighborhood of Barracas in various venues, including his own, “Una noche de garufa”, which he opened with his friend, the industrialist Luis Bettinelli.

His first composition, published in 1912, was an immediate great success.

Other compositions of remarkable inspiration followed, although they are not as well known today as they should be: “Nariz”, dedicated to his “amiguita” Delia López; “Rey de los bordoneos”, dedicated to his musicians; “Maturango”; “Chúmbale” and the vals “Notas del corazón”, dedicated to his mother.

In 1910 the first recordings of an orchestra with the bandoneon, directed by Vicente Greco, were released by Columbia Records

In 1910 the first recordings of an orchestra with the bandoneon, directed by Vicente Greco, were released by Columbia Records. The great acceptance by audiences of these recordings propitiated the appearance of numerous recording labels competing for the market. Arolas started recording in 1912 for Poli-phon, with Tito Roccatagliatta on violin, Vicente Pecci on flute, and Emilio Fernández on guitar.

In 1912 he started playing in downtown Buenos Aires and soon included in his formation the great pianist and composer José Martínez, author of “

El cencerro”, “

La torcacita”, “

Pablo", “

Punto y coma”, “

Canaro”, among many great tangos, to play at the cabaret Royal Pigall, on Corrientes Street 825.

This same year,

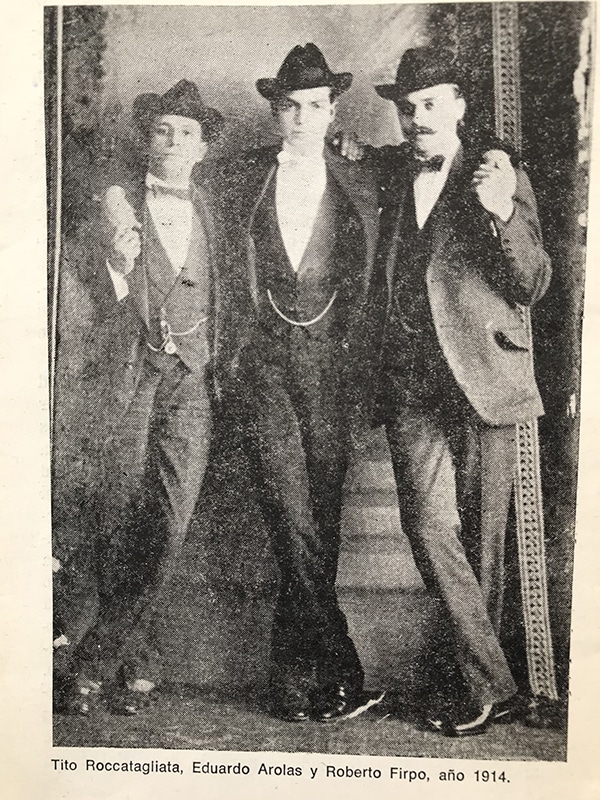

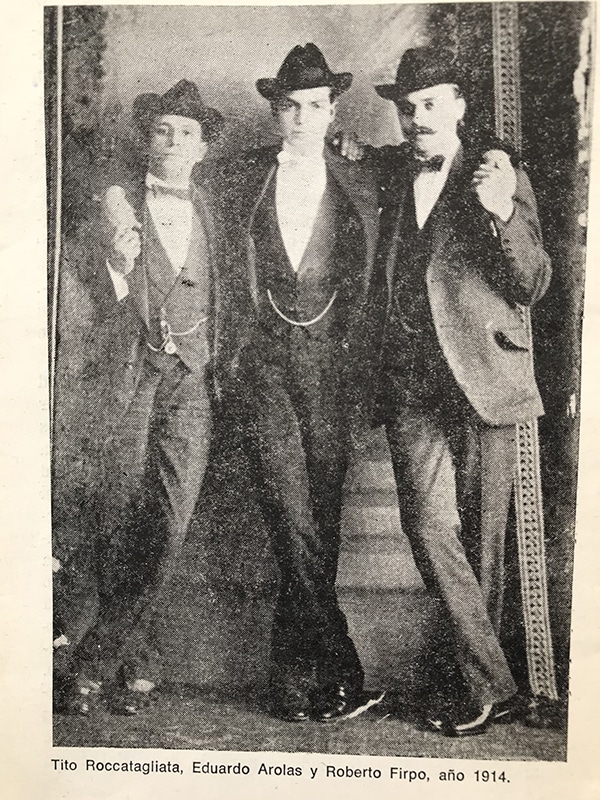

Roberto Firpo called Arolas and Roccatagliatta to play with him at the famous cabaret Armenonville. Later, Arolas distanced himself from Firpo and had a sign at his presentations that clarified, “We don’t play Firpo’s compositions”. But “Fuegos artificiales" became a great outcome from this encounter.

Firpo still went on to record many of Arolas’ tangos.

Let's listen to the magnificent rendition of "Fuegos artificiales" by

Anibal Troilo y su Orquesta Típica, 1945:

After taking distance from Firpo, in 1914, Afro-American Harold Philips played the piano for a while at Arolas' orchestra.

In 1915, Arolas played with Agustin Bardi on piano and Roccatagliatta on violin.

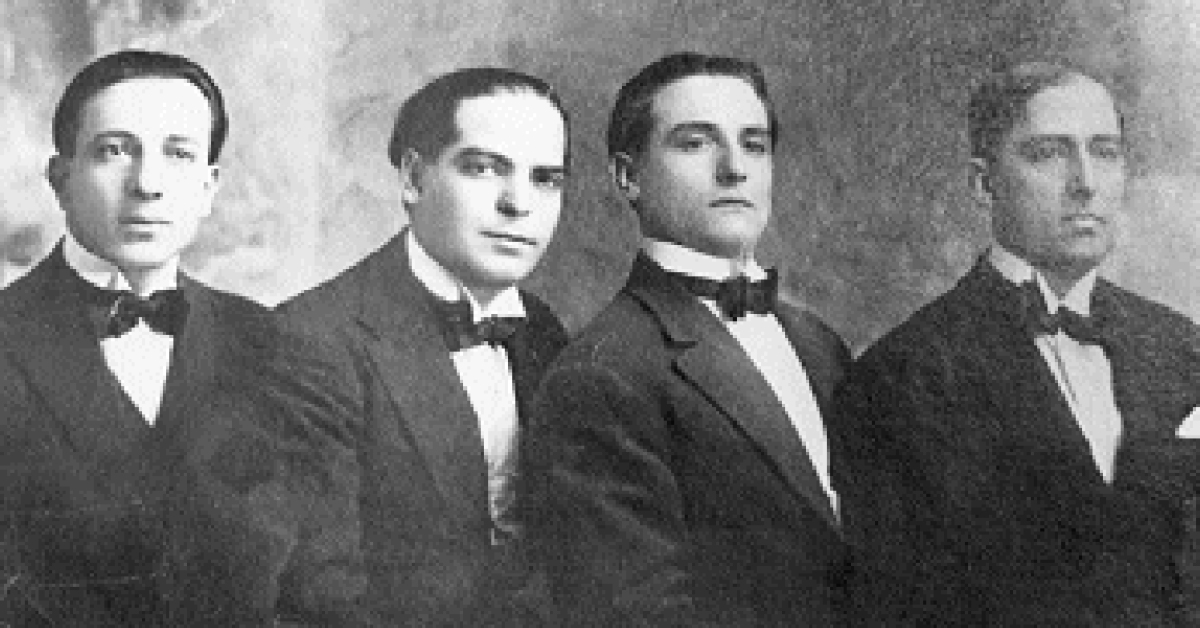

In 1916, he formed a trio with Roccatagliatta on violin and Juan Carlos Cobián on piano at the cabarets Montmartre, L’Abbaye, and Fritz, all located downtown. This trio sometimes expanded to a quartet to include a violoncello. They also made a tour of the province of Córdoba.

In Buenos Aires, the trio was hired to play at parties and dancings of the Buenos Aires’ upper-class mansions, embassies, and select clubs. At these kinds of gigs, any interaction between musicians and guests was not tolerated, a rule that Arolas never accepted, which resulted in his replacement by

Osvaldo Fresedo.

Between 1913 and 1916, his musical composition and production showed evident improvement due to his musical studies and the achieved experience of his profession. He consolidated his fame, taking his orchestra to the level of the most prominent ones, leaving the neighborhood cafés, playing on Corrientes Street, and at the luxurious places of Palermo neighborhood, in the interior of Argentina, and in Montevideo.

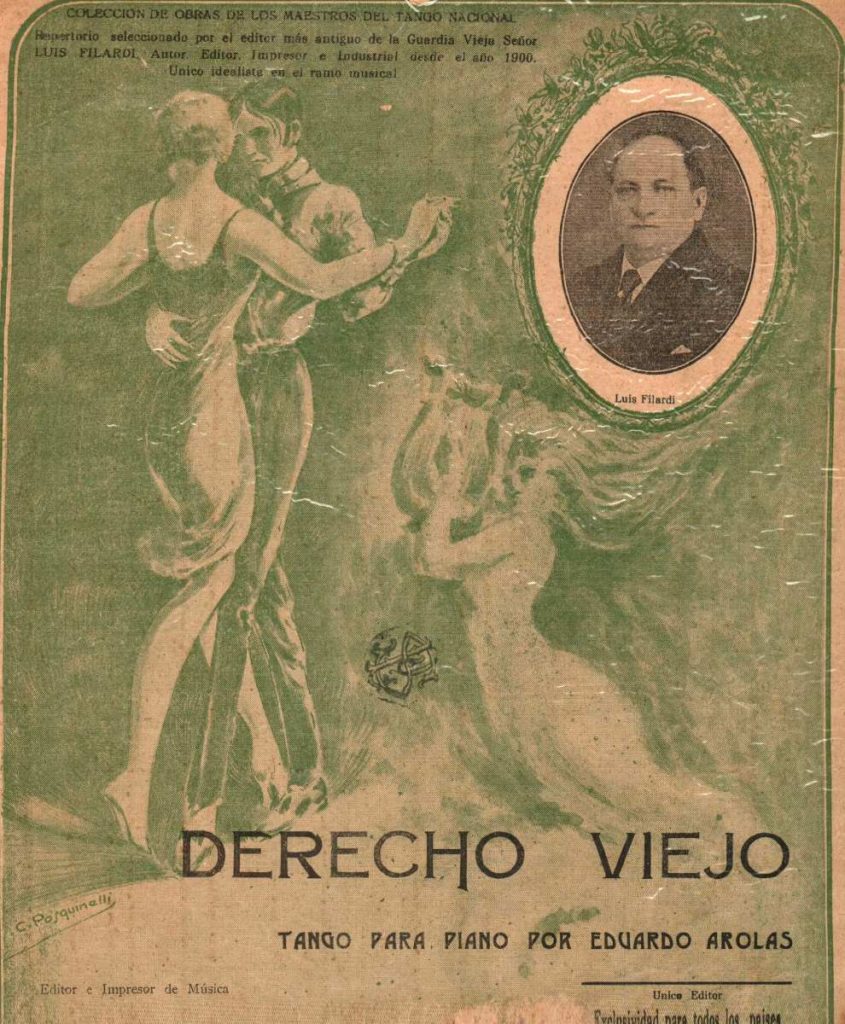

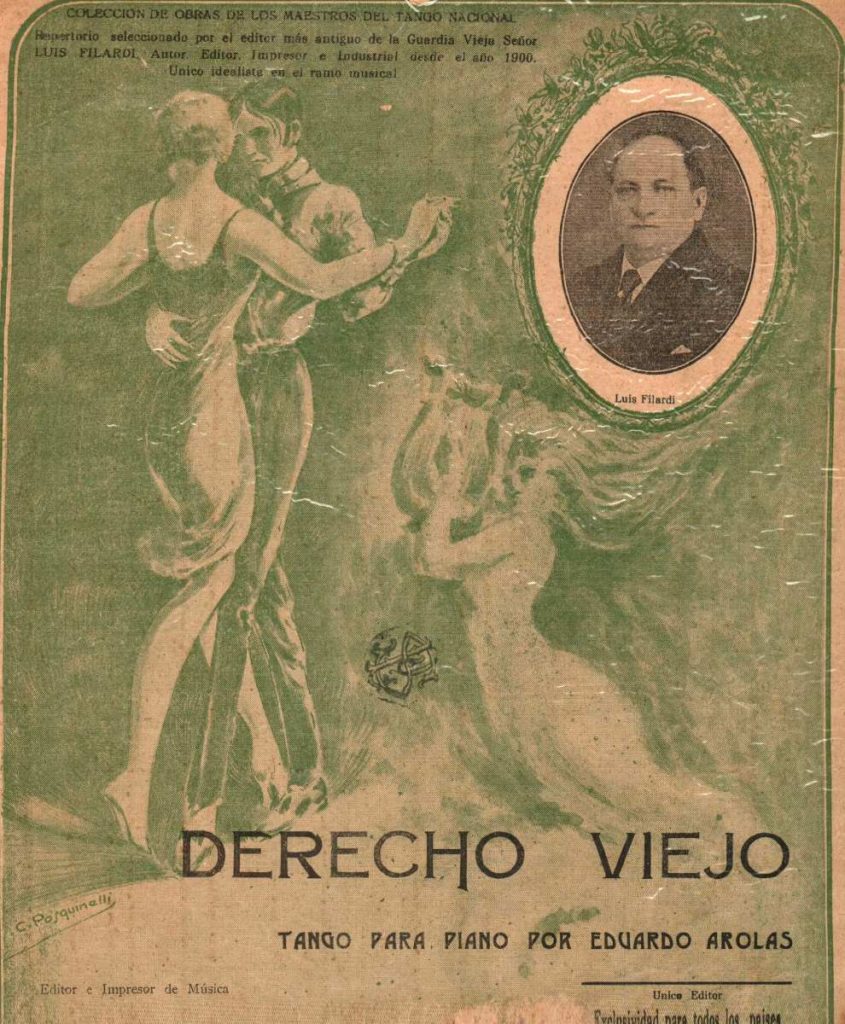

Some of the compositions of this period, among many that have today been forgotten, are “Derecho viejo”-played here by

Osvaldo Pugliese y su Orquesta Típica in 1945:

“La guitarrita” -by

Juan D'Arienzo in 1936:

“Rawson” -again, by

El Rey del Compás:

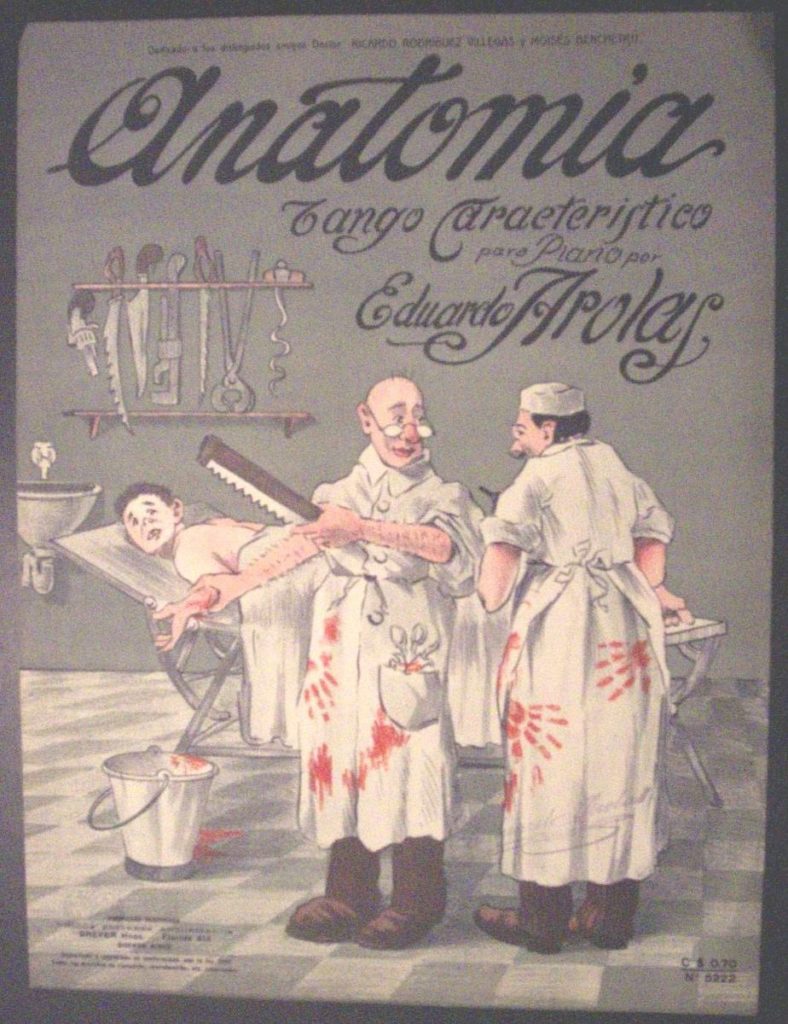

“Araca” and “Anatomía”.

Specifically, regarding the song “Araca”, there is only one magnificent rendition recorded by “Cuarteto Victor de la Guardia Vieja” in 1936, with Francisco Pracánico on piano, Ciriaco Ortiz on bandoneon, and Cayetano Puglisi and Antonio Rossi on violins.

The third and last group of compositions, from 1917 to 1923, showed an even further musical evolution, deeper in feelings, nostalgic, almost crying with masculine vulnerability, playing with his characteristic rhythmic phrasing. These works were influenced by the break up with his lover Delia López, who ended up involved with his brother, and his subsequent submersion into alcoholism and chronic sadness. Among them: from 1917, “Comme il faut” -here is the recording of

Anibal Troilo in 1938:

and “Retintin”, called first "Qué hacés, qué hacés, che Rafael!", dedicated to his violin player, friend and secretary, Rafael Tuegols. The whole orchestra sang the name of the song at the performances -here by

Juan D'Arienzo y su Orquesta Típica, with

Rodolfo Biagi on piano:

Less known from this same year are “Marrón glacé (Moñito)”, dedicated to the racing horse of his friend Emilio de Alvear; “El chañar”, of which there is a rendition by

Alfredo De Angelis, recorded during the Golden Era:

and “Taquito”, recorded only by Arolas.

In 1917, he formed a quintet with Juan Luis Marini on piano, Rafael Tuegols, Atilio Lombardo on violins, and Alberto Paredes on violoncello and recorded for Victor with an advantageous contract. Unusual for the time, he included the voice of Francisco Nicolás Bianco, “Pancho Cueva”, on two recordings, only matched by the contemporary recording of Gardel-Razzano with

Firpo at “El moro”. Bianco, who later also recorded with Firpo, was a famous payador who used the lunfardo jargon in his performances and was the brother of Eduardo Bianco. This great conductor played tangos in Europe.

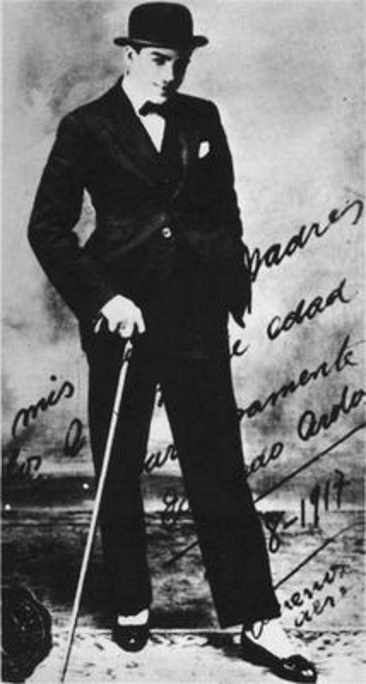

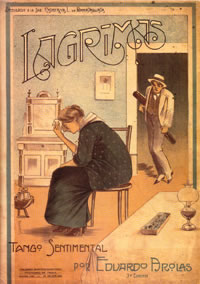

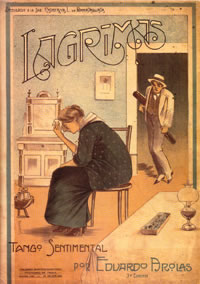

The composition cover artwork for the song “Lágrimas” deserves a special mention because of Arolas' self-portrait:

Dedicated to the mother of his colleague and violinist Tito Roccatagliata, combined a delicious rhythmic first part with a profoundly emotional second part.

Ricardo Tanturi recorded it in 1941:

In 1918 his orchestra was formed with him on the first bandoneon and conductor, Manuel Pizzarro on the second bandoneon, Rafael Tuegols on the first violin, Horacio Gomila on the second violin, Roberto Goyeneche on piano, and Luis Bernstein on double bass. This was the peak of his career, playing in both Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Soon, Julio De Caro joined his orchestra.

1918 brought us two tangos eminently rhythmic: “Catamarca”, initially called “Estocada a fondo”, of which

Carlos Di Sarli left us a magnificent rendition in 1940:

The other tango is “Dinamita", which we can hear in the rendition of 1918 by

Roberto Firpo:

Here we can appreciate authentic rhythmic dynamite, his peculiar way of playing with the melody, and its manifested advanced compositional techniques, using already the same “canyengueadas” that we hear in the arrangements of

Osvaldo Pugliese and Astor Piazzolla many decades later.

That same year, Arolas met Pascual Contursi in Montevideo. From this encounter, they produced “Qué querés con esa cara”, lyrics that Contursi wrote for Arolas’ “La guitarrita”, recorded by

Carlos Gardel:

This year culminated with one of his immortal compositions: “Maipo”, of supreme beauty, with a first part truly sublime, of pathetic depth, tearing, and the second part of felt sadness and deep emotions. Let’s dance to

El Rey de Compás Juan D’Arienzo’s recording of this tango in 1939:

1919 began with no less than “El Marne”, a true concerto of advanced structure for its time. It needed to wait for qualified musicians to deliver the message of its notes. We remain here at the same tanda, with the Maestro

D’Arienzo and Juan Polito on piano:

The productivity of Arolas is astounding. His fabulous inspiration keeps on giving: “Cosa papa”, which he only recorded on his last recording, in line with his best authorial achievements.

“Rocca”, dedicated to his great friend, the landowner, and keeper of Argentine traditions, Santiago H. Rocca, in which music sheet edition, we can see a portrait of the homaged, beautified by a fine drawing from Arolas.

There are no recordings that we know of this tango, but we are lucky to hear Horacio Asborno’s pianola playing it:

https://youtu.be/oysQmH3QR3Q“Viborita” is another of his delicate tangos, with the peculiarity of having only two parts, without a trio, as was his custom. Recorded in 1920 for the first time by the Orquesta Típica Select of

Osvaldo Fresedo. Its music sheet was not published until after 1930, when the nephew of Arolas received a pack with manuscripts. That is why it appears published as posthumous work. A superb rendition of this tango to dance at the milongas is the one recorded by

Francisco Lomuto in 1944:

“De vuelta y media”, of outstanding beauty, from which we are lucky to hear the author's recording:

And “El Gaucho Néstor”, included only in his recordings for Victor:

In 1919 he was hired to play at Montevideo’s Carnaval celebrations at the head of a big orchestra.

https://escuelatangoba.com/marcelosolis/history-of-tango-part-9-eduardo-arolas-the-evolution-of-tango-music/

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth.

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth. The following year, in 1898,

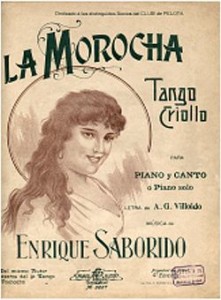

The following year, in 1898,  Enrique Santos Discépolo's father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote

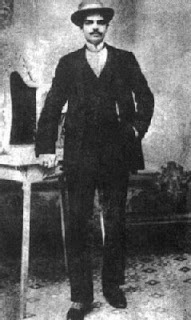

Enrique Santos Discépolo's father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote  Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many "El padre del Tango" (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper "La Razón" in 1917, we know that he was "cuarteador" of "La Calle Larga" (The Long Street, today's Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

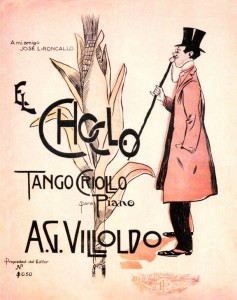

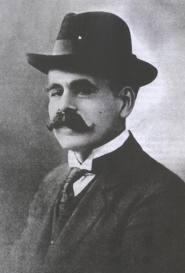

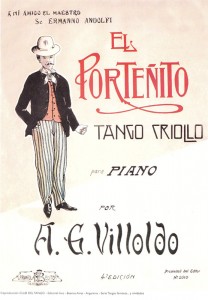

Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many "El padre del Tango" (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper "La Razón" in 1917, we know that he was "cuarteador" of "La Calle Larga" (The Long Street, today's Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang  On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola

On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with

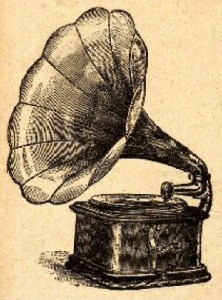

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with  On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The "arm" of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner's disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The "arm" of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner's disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

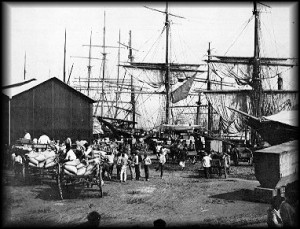

The first Argentinean Presidents promoted the immigration of the European workforce, defeated the indigenous people who had still claimed part of the Argentine territory, favored an economic model of production and export of agricultural goods following British-led ideas of the international division of work, and invested in the technology and infrastructure that made possible such model. A modern port was constructed in Puerto Madero, and a railroad network transported the whole production of the entire country to this port. Buenos Aires greatly benefitted from these changes and grew exponentially. Between 1871 and 1915, Argentina received 5 million immigrants, mostly Europeans. Almost all of them stayed in Buenos Aires.

The first Argentinean Presidents promoted the immigration of the European workforce, defeated the indigenous people who had still claimed part of the Argentine territory, favored an economic model of production and export of agricultural goods following British-led ideas of the international division of work, and invested in the technology and infrastructure that made possible such model. A modern port was constructed in Puerto Madero, and a railroad network transported the whole production of the entire country to this port. Buenos Aires greatly benefitted from these changes and grew exponentially. Between 1871 and 1915, Argentina received 5 million immigrants, mostly Europeans. Almost all of them stayed in Buenos Aires. All these new arrivals to Buenos Aires had few resources and were very poor. They could only afford housing in the poorest neighborhoods, where the Afro-Argentineans, descendants of the African slaves, had been populating since 1813's abolition of slavery. They were the locals. If any newcomer wanted to know something about Buenos Aires, they had to ask the Afro-Argentineans, who, before this massive immigration, constituted one-third of the population.

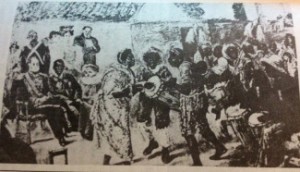

All these new arrivals to Buenos Aires had few resources and were very poor. They could only afford housing in the poorest neighborhoods, where the Afro-Argentineans, descendants of the African slaves, had been populating since 1813's abolition of slavery. They were the locals. If any newcomer wanted to know something about Buenos Aires, they had to ask the Afro-Argentineans, who, before this massive immigration, constituted one-third of the population. Between 1820 and 1850, before the Argentine Constitution was written and immigration was promoted, Argentina was under the administration of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this time, the Afro-Argentineans enjoyed a period of greater participation and freedom of expression. Rosas was a landowner in the province of Buenos Aires with a perfect resume. When he was only thirteen, he fought heroically against the English invasions. Later on, he proved to be a very efficient administrator of cattle ranches and a successful businessman. Rosas created, financed, and trained his militia of gauchos, which would go on to be integrated into the state as an official regiment. They soon earned a reputation for being highly disciplined, and Rosas was able to establish order at the border with the indigenous populations. In 1819, Rosas put this militia at the province's governor's service to quell an uprising against him. This is how Rosas became known as “El Restaurador de las Leyes” (”The Restorer of Law’).

Between 1820 and 1850, before the Argentine Constitution was written and immigration was promoted, Argentina was under the administration of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this time, the Afro-Argentineans enjoyed a period of greater participation and freedom of expression. Rosas was a landowner in the province of Buenos Aires with a perfect resume. When he was only thirteen, he fought heroically against the English invasions. Later on, he proved to be a very efficient administrator of cattle ranches and a successful businessman. Rosas created, financed, and trained his militia of gauchos, which would go on to be integrated into the state as an official regiment. They soon earned a reputation for being highly disciplined, and Rosas was able to establish order at the border with the indigenous populations. In 1819, Rosas put this militia at the province's governor's service to quell an uprising against him. This is how Rosas became known as “El Restaurador de las Leyes” (”The Restorer of Law’). He became the Governor of the province of Buenos Aires and, between 1835 and 1852, was the prominent leader of the Argentinean Confederation. This period of Argentina's history is called the “Era of Rosas.” He obtained the necessary support for his administration from the poorer sectors of the population of the City of Buenos Aires (integrated for a majority of Afro-Argentineans), and the gauchos of the countryside close to the City (many of whom were also Afro-Argentinean.) During his tenure, Rosas attended the “candombes” (celebrations) of the Afro-Argentineans as an honored guest. Also, during this period, the carnivals began in Buenos Aires.

He became the Governor of the province of Buenos Aires and, between 1835 and 1852, was the prominent leader of the Argentinean Confederation. This period of Argentina's history is called the “Era of Rosas.” He obtained the necessary support for his administration from the poorer sectors of the population of the City of Buenos Aires (integrated for a majority of Afro-Argentineans), and the gauchos of the countryside close to the City (many of whom were also Afro-Argentinean.) During his tenure, Rosas attended the “candombes” (celebrations) of the Afro-Argentineans as an honored guest. Also, during this period, the carnivals began in Buenos Aires. In the origins of social dances, we observe no physical contact between partners; then they take each other hands, developing the “minuet” during the 1600s, which led to dancing in each other's arms, with the “waltz” in the 1700s. The direction of the evolution of social partner dancing becomes evident: a closing of the distance between the partners that culminates in the embrace of Tango.

In the origins of social dances, we observe no physical contact between partners; then they take each other hands, developing the “minuet” during the 1600s, which led to dancing in each other's arms, with the “waltz” in the 1700s. The direction of the evolution of social partner dancing becomes evident: a closing of the distance between the partners that culminates in the embrace of Tango. This technique soon became the characteristic dance of the poorest inhabitants of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rosario, and the villages located south of Buenos Aires in an area known as “Barracas al sur”, Avellaneda, and Sarandí.

This technique soon became the characteristic dance of the poorest inhabitants of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rosario, and the villages located south of Buenos Aires in an area known as “Barracas al sur”, Avellaneda, and Sarandí. The Andalusian-style houses of the Southern side of Buenos Aires, San Telmo, and La Boca were soon creatively transformed into rooms to rent.

The Andalusian-style houses of the Southern side of Buenos Aires, San Telmo, and La Boca were soon creatively transformed into rooms to rent. In 1871, Buenos Aires suffered a yellow fever epidemic that killed 8% of its population, most living in these houses. The situation was so dire (with more than 13,000 people dying in 4 months) that it was necessary to open a new cemetery in the area of La Chacarita.

In 1871, Buenos Aires suffered a yellow fever epidemic that killed 8% of its population, most living in these houses. The situation was so dire (with more than 13,000 people dying in 4 months) that it was necessary to open a new cemetery in the area of La Chacarita. The first Andalusian tango to reach mass popularity was composed in Argentina in 1874. The title is

The first Andalusian tango to reach mass popularity was composed in Argentina in 1874. The title is