How Tango came to be is unknown. We have information about the history leading up to the rise of Argentina as a state. From these facts, we can only speculate about how Tango came to be.

In 1805 and again in 1807, England tried to invade Buenos Aires but was repealed successfully by the population, not by the Spanish army, which abandoned the city. This paved the way for ideas of independence, eventually leading to the Colonial system's end. After a war against Spain and a civil war, the Argentine Republic unified during the decade of 1860. Most of the references related to Tango point to this time to signify its origins.

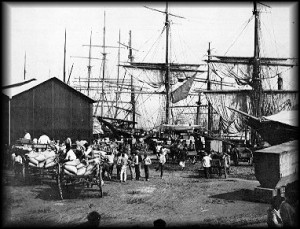

The first Argentinean Presidents promoted the immigration of the European workforce, defeated the indigenous people who had still claimed part of the Argentine territory, favored an economic model of production and export of agricultural goods following British-led ideas of the international division of work, and invested in the technology and infrastructure that made possible such model. A modern port was constructed in Puerto Madero, and a railroad network transported the whole production of the entire country to this port. Buenos Aires greatly benefitted from these changes and grew exponentially. Between 1871 and 1915, Argentina received 5 million immigrants, mostly Europeans. Almost all of them stayed in Buenos Aires.

The first Argentinean Presidents promoted the immigration of the European workforce, defeated the indigenous people who had still claimed part of the Argentine territory, favored an economic model of production and export of agricultural goods following British-led ideas of the international division of work, and invested in the technology and infrastructure that made possible such model. A modern port was constructed in Puerto Madero, and a railroad network transported the whole production of the entire country to this port. Buenos Aires greatly benefitted from these changes and grew exponentially. Between 1871 and 1915, Argentina received 5 million immigrants, mostly Europeans. Almost all of them stayed in Buenos Aires.Buenos Aires, known at that time as “La Gran Aldea” (“The Great Village”), also received other immigrants from the countryside who had been displaced. The gauchos’ natural environment was the Pampas, which became the private property of the new landowners. Also, the “chinas” were indigenous women whose men were killed in battle, defending their territory.

All these new arrivals to Buenos Aires had few resources and were very poor. They could only afford housing in the poorest neighborhoods, where the Afro-Argentineans, descendants of the African slaves, had been populating since 1813's abolition of slavery. They were the locals. If any newcomer wanted to know something about Buenos Aires, they had to ask the Afro-Argentineans, who, before this massive immigration, constituted one-third of the population.

All these new arrivals to Buenos Aires had few resources and were very poor. They could only afford housing in the poorest neighborhoods, where the Afro-Argentineans, descendants of the African slaves, had been populating since 1813's abolition of slavery. They were the locals. If any newcomer wanted to know something about Buenos Aires, they had to ask the Afro-Argentineans, who, before this massive immigration, constituted one-third of the population. Between 1820 and 1850, before the Argentine Constitution was written and immigration was promoted, Argentina was under the administration of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this time, the Afro-Argentineans enjoyed a period of greater participation and freedom of expression. Rosas was a landowner in the province of Buenos Aires with a perfect resume. When he was only thirteen, he fought heroically against the English invasions. Later on, he proved to be a very efficient administrator of cattle ranches and a successful businessman. Rosas created, financed, and trained his militia of gauchos, which would go on to be integrated into the state as an official regiment. They soon earned a reputation for being highly disciplined, and Rosas was able to establish order at the border with the indigenous populations. In 1819, Rosas put this militia at the province's governor's service to quell an uprising against him. This is how Rosas became known as “El Restaurador de las Leyes” (”The Restorer of Law’).

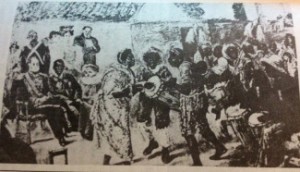

Between 1820 and 1850, before the Argentine Constitution was written and immigration was promoted, Argentina was under the administration of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this time, the Afro-Argentineans enjoyed a period of greater participation and freedom of expression. Rosas was a landowner in the province of Buenos Aires with a perfect resume. When he was only thirteen, he fought heroically against the English invasions. Later on, he proved to be a very efficient administrator of cattle ranches and a successful businessman. Rosas created, financed, and trained his militia of gauchos, which would go on to be integrated into the state as an official regiment. They soon earned a reputation for being highly disciplined, and Rosas was able to establish order at the border with the indigenous populations. In 1819, Rosas put this militia at the province's governor's service to quell an uprising against him. This is how Rosas became known as “El Restaurador de las Leyes” (”The Restorer of Law’). He became the Governor of the province of Buenos Aires and, between 1835 and 1852, was the prominent leader of the Argentinean Confederation. This period of Argentina's history is called the “Era of Rosas.” He obtained the necessary support for his administration from the poorer sectors of the population of the City of Buenos Aires (integrated for a majority of Afro-Argentineans), and the gauchos of the countryside close to the City (many of whom were also Afro-Argentinean.) During his tenure, Rosas attended the “candombes” (celebrations) of the Afro-Argentineans as an honored guest. Also, during this period, the carnivals began in Buenos Aires.

He became the Governor of the province of Buenos Aires and, between 1835 and 1852, was the prominent leader of the Argentinean Confederation. This period of Argentina's history is called the “Era of Rosas.” He obtained the necessary support for his administration from the poorer sectors of the population of the City of Buenos Aires (integrated for a majority of Afro-Argentineans), and the gauchos of the countryside close to the City (many of whom were also Afro-Argentinean.) During his tenure, Rosas attended the “candombes” (celebrations) of the Afro-Argentineans as an honored guest. Also, during this period, the carnivals began in Buenos Aires."Abuelita Dominga era muy vieja

y vivía en el barrio de los candombes.

Del carnaval de Rosas no se olvidaba

al cantar esta copla roja de amores:

Rosa morena,

de la estrella federal,

yo se que tu alma está llena

de un pasión que es mortal.

Rosa morena,

todos la vieron pasar,

en su garganta morena

sangraba un rojo collar.

Abuelita Dominga siempre lloraba

al recordar la historia de amor y sangre.

Y me dio esta guitarra para que un día,

la cante como nunca la cantó nadie.

Rosa morena,

muerta en los cercos en flor

la vio una noche serena

todo el Barrio del Tambor.

Rosa perdida

aún dice el viejo cantar

que le quitaron la vida

porque quiso traicionar."

“Rosa Morena (Abuelita Dominga)”, Héctor Blomberg and Enrique Maciel.

“Están de fiesta

en la calle Larga

los mazorqueros

de Monserrat.

Y entre las luces

de las antorchas,

bailan los negros

de La Piedad.

Se casa Pancho,

rey del candombe,

con la mulata

más federal,

que en los cuarteles

de la Recova,

soñó el mulato

sentimental.

Baila, mulata linda,

bajo la luna llena,

que al chi, qui, chi del chinesco,

canta el negro del tambor.

Baila, mulata linda,

de la divisa roja,

que están mirando los ojos

de nuestro Restaurador.

Ya esta servida

la mazamorra

y el chocolate

tradicional

y el favorito

plato de locro,

que ha preparado

un buen federal.

Y al son alegre

de tamboriles

los novios van

a la Concepción

y al paso brinda,

la mulateada,

por la más Santa

Federación.”

“La mulateada”, Julio Eduardo Del Puerto and Carlos Pesce.

Juan Manuel de Rosas’ regime affected all aspects of life in Buenos Aires and the culture. After his fall in 1852, local famous actors under his regime were dismissed, and the theaters of the City received foreign companies in their place. The Spanish theater companies from Andalusia were the most popular then, with the “sainete” being the primary genre offered by these companies. This genre comprised shorter pieces, including humor, songs, and dance elements. Soon, the music and dance of Tango could be seen on these stages.

Also, after Rosas was exiled, the candombes were prohibited in open spaces, so the Afro-Argentineans had to continue them inside. This change of venue forced them to dance closer to each other, shaping the choreographic elements of their dance, which eventually fit the embrace of Tango. During this period, “Tango” referred to any dance performed by the Afro-Argentineans.

All the necessary elements for Tango to appear were there: the Great City of Buenos Aires, the Afro-Argentine culture, the criollo and the gaucho, the native “chinas”, the massive immigration, the reconciliation with the Spanish heritage after the end of the War of Independence, and the open door to the rest of the world through the port.

In modern society, dancing is viewed as a specialized activity, such as a profession or a hobby. For the people of the 1800s, dance was integrated into everyday life. A person was not particular because they danced, but they stood out if they did not or could not dance.

The Renaissance was the beginning of dance as a modern social activity. Before the Renaissance, dance was a purely ritual activity, intending to maintain a connection between the human realm and the Cosmos, which involved mythological and religious connotations and rationales.

Then with the development of the modern city and its lifestyle, and the consequent secularization of all aspects of life, dance assumed the role of facilitating social interaction.

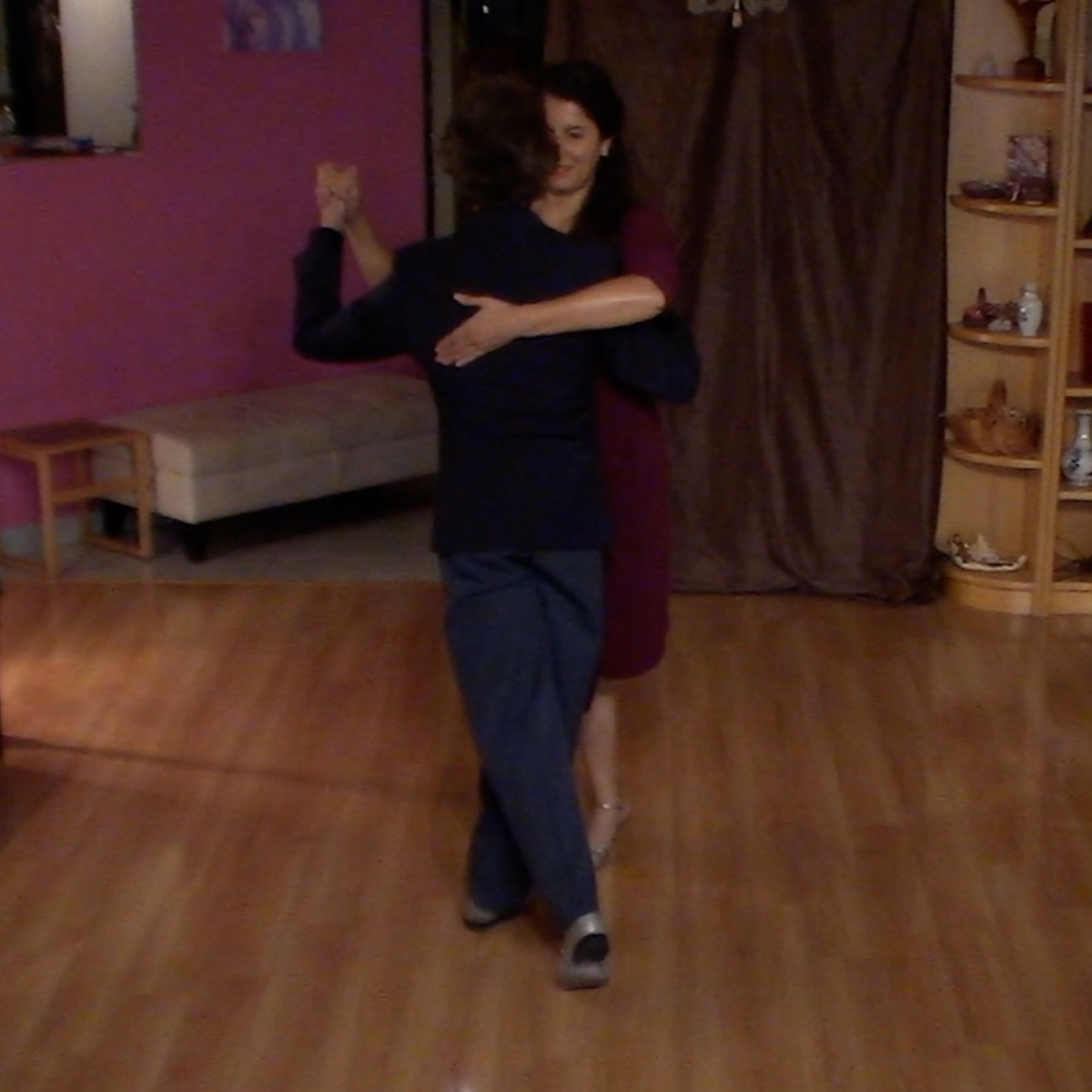

In the origins of social dances, we observe no physical contact between partners; then they take each other hands, developing the “minuet” during the 1600s, which led to dancing in each other's arms, with the “waltz” in the 1700s. The direction of the evolution of social partner dancing becomes evident: a closing of the distance between the partners that culminates in the embrace of Tango.

In the origins of social dances, we observe no physical contact between partners; then they take each other hands, developing the “minuet” during the 1600s, which led to dancing in each other's arms, with the “waltz” in the 1700s. The direction of the evolution of social partner dancing becomes evident: a closing of the distance between the partners that culminates in the embrace of Tango.There are two explanations for why the embrace happened in Tango, which are not contradictory. The first is the eclectic origins of the dance, which combined techniques of opposite tendencies, like the continuous movement in acceptance of the inertia, characteristic of waltz, and the “figures”, detention of the movement opposing the inertia, characteristic of the dances with separate partners or solo dancers, performed, among others, in the Afro-Argentinean and Andalusian dances. The greater communication made possible in the embrace produced a social partner dance that could have both the partners united in each other's arms and the figures from the stops of the solo dancers. The other explanation is emotional: the consolation the embrace gave all these humans left alone by displacement, economic exile, and destruction of their families, cultures, and lifestyles.

Other characteristics of the new dance were that it was improvised, favoring the skill and creativity of the dancers, their spontaneity, in contrast with the repetition of choreographed formulas that the other dances demanded; and the innovation that the woman walks backward, which contradicted all previous approaches to partner dancing. These elements are rooted in the body language of the criollos, men and women trained in short knife fencing. Due to a cultural demand and the historical realities of the time, knowing how to fight was necessary, just as today it is considered necessary to read and write. In a historical situation of the rapid transformation of the government and institutions, no reliable protection was provided to the people, their families, or their property.

Before the British, who the Argentinean government commissioned to construct the railroad network, brought futbol (“football” in England, “soccer” in the United States) to Argentina (effectively making it the most popular sport), the criollos of Buenos Aires practiced “visteo.” Visteo is a variation of fencing using a wooden stick burned in one end, or the index finger painted with grease or ashes, to mark the white shirt of the opponent. This is something that was inherited from the gauchos. The popularity of this practice prepared the Porteños of the 1800s with the necessary skills to create the dance of Tango.

The characteristic elements of the dance of Tango were referred to as “cortes y quebradas” (cuts and breaks).

This technique soon became the characteristic dance of the poorest inhabitants of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rosario, and the villages located south of Buenos Aires in an area known as “Barracas al sur”, Avellaneda, and Sarandí.

This technique soon became the characteristic dance of the poorest inhabitants of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rosario, and the villages located south of Buenos Aires in an area known as “Barracas al sur”, Avellaneda, and Sarandí.These women and men received the names: “chinas” and “compadritos.”

The massive immigration in Buenos Aires was intended to populate the countryside. Still, a failure in the implementation of the necessary policies, corruption, and the “Panic of 1873” (the great financial crisis that triggered a worldwide economic depression) conspired to detain almost the entire human wave in “The Great Village.” The City was unprepared to receive this amount of people, and housing quickly became one of the most urgent problems.

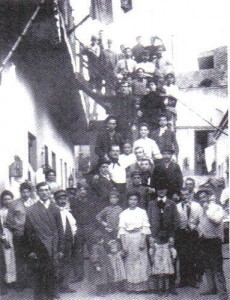

The Andalusian-style houses of the Southern side of Buenos Aires, San Telmo, and La Boca were soon creatively transformed into rooms to rent.

The Andalusian-style houses of the Southern side of Buenos Aires, San Telmo, and La Boca were soon creatively transformed into rooms to rent.This type of construction, typical of the Colonial time, constituted a string of rooms aligned one after the other, with doors that opened to a patio or corridor connecting them. Their owners made each room a separate apartment to rent.

The huge demand for rooms made them expensive, so sometimes more than one family would rent one room and further divide it to make it affordable. This created a very crowded living unit called “conventillo.”

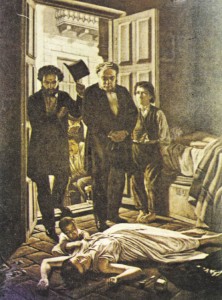

In 1871, Buenos Aires suffered a yellow fever epidemic that killed 8% of its population, most living in these houses. The situation was so dire (with more than 13,000 people dying in 4 months) that it was necessary to open a new cemetery in the area of La Chacarita.

In 1871, Buenos Aires suffered a yellow fever epidemic that killed 8% of its population, most living in these houses. The situation was so dire (with more than 13,000 people dying in 4 months) that it was necessary to open a new cemetery in the area of La Chacarita.Many immigrants were male because they did not want to risk their families in the adventures of a “new world.” This created the conditions for the rise of prostitution as a very profitable business.

After the 1871 yellow fever epidemic, the authorities of Buenos Aires became more concerned with public health. Among many public health measures, prostitution was regulated. The unintended outcome was the differentiation between foreign women and the locals. Foreign women, who did not understand the language and the culture, were lured into being sex slaves by an international network of human traffickers and had to accept these regulations, fees, and taxation. The locals, Afro-Argentineans and native “chinas,” together with the Spanish and Italians, went into hiding. This also satisfied the demand of two different sectors of the market, per their purchase power, making the “loras” (“parrots”, due to the language barrier) the better off and the “chinas” (Quechua word for “woman”) the less favored. The legal business, called “casas de tolerancia” (“houses of tolerance”), were located downtown, in the area of Corrientes Street, San Nicolas, Palermo, San Cristobal, and Barracas. The clandestine ones were called “cuartos de chinas.”

"Milonga del tiempo guapo, milongón de rompe y raja,

la bulla del empedrado va marcando tu canción;

soy porteño del 80 y al compás de tu canyengue

desfilan por mi memoria los recuerdos en montón.

Te conocí en los fortines

que cuidaban la frontera

reclamando los amores

de una china cuartelera.

Animando las retretas

del Parque de Artillería

y en la barriada bravía

de las Barracas del Sur.

Milonga del tiempo guapo, milongón de los milicos,

de “kepises” requintados y bombachas de carmín;

con tu música sencilla fuiste ley de los porteños,

grito de los cuarteadores y alma del piringundín.

Te conocí en los corrales

de los viejos Mataderos,

hecha jerga en los quillangos

del recao de un forastero.

tu canto fue la corneta

del cochero del tranvía

y el Palermo de avería

tu escuela sentimental."

"Del tiempo guapo", Vicente Fiorentino and Marcelo De La Ferrere.

The demand was always greater than the supply, meaning customers had to wait. The owners of these houses soon realized that they needed to offer something to these customers while they waited, to keep them from leaving and to entertain them. They began to hire musicians as a form of entertainment. The most popular music at the time was polka, habanera, milonga and a new kind of rhythm called… tango. Sometimes the men who were waiting would dance, which led the owners to the realization that perhaps the dance in itself could generate business.

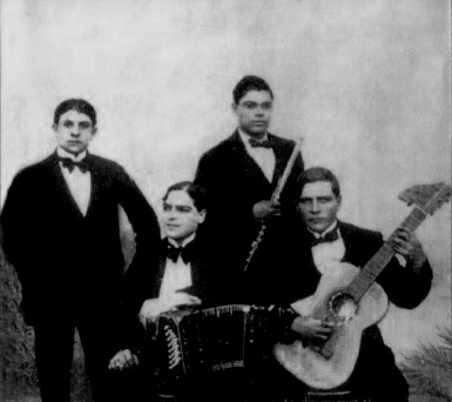

The first “academias” began to open during the 1870s. These were places where men could go and dance with a superb female dancer, improve their skills, and try new moves, all for a fixed price per song. These women shared the customer’s pay with the owner of the hall. The better dancers were more in demand and would dance nonstop for several hours, song after song, man after man. They did not need to be pretty or possess any other quality besides being great dancers. The academias were located mainly in Constitución and San Cristobal and popular in the City of Rosario. The owners and managers of the academias were mostly Afro-Argentineans.

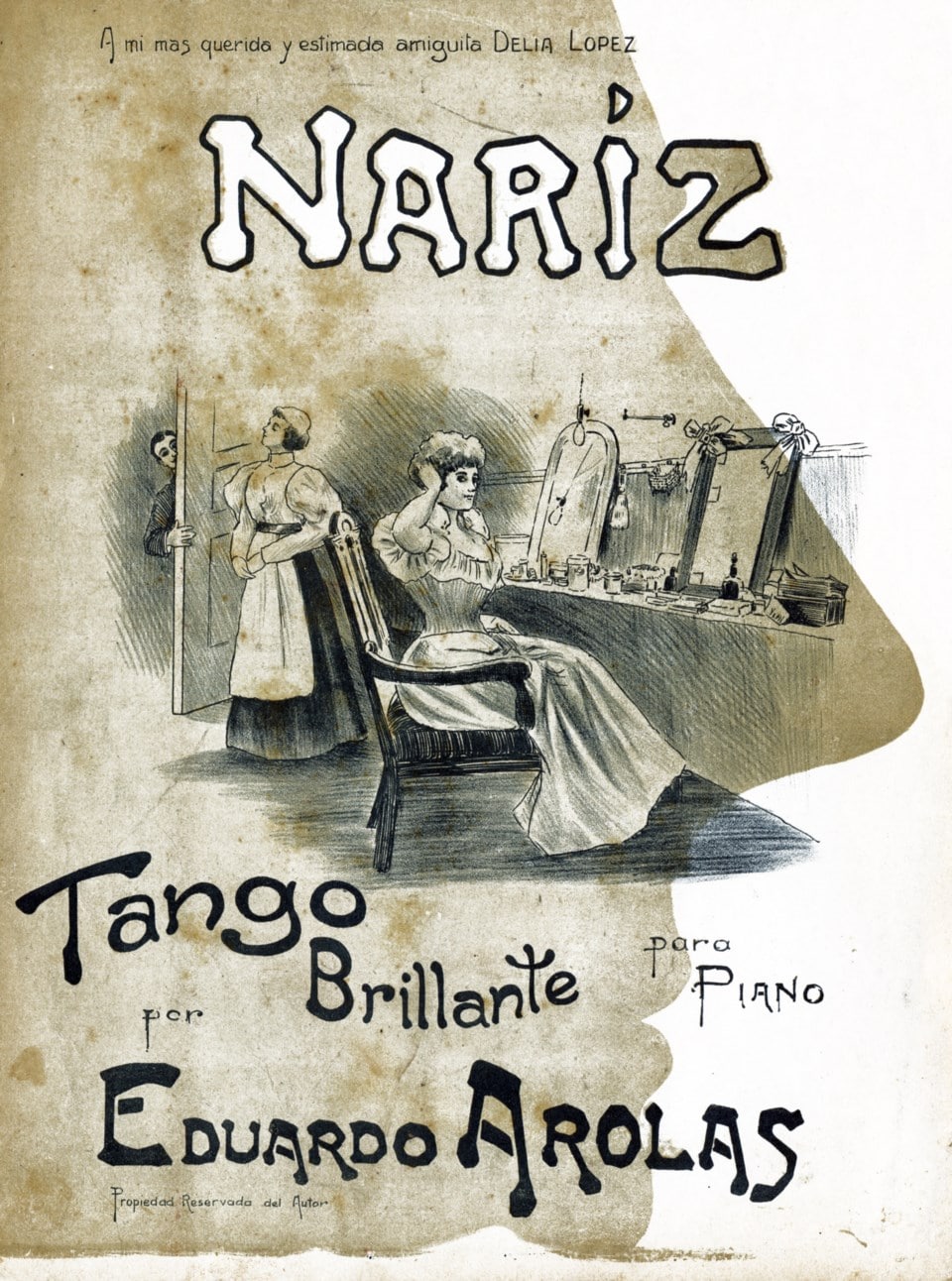

Outside the circuit of academias, in 1857, the Spanish musician Santiago Ramos provided a distinctive Andalusian contribution, which in turn recognized Afro-Cuban and African roots. He composed one of the first tango-flavored songs, "Tomá mate, che" a proto-tango with “Rioplatense" lyrics and Andalusian-style musical arrangements. It was part of the “sainete” “The Gaucho of Buenos Aires,” which premiered at the Teatro de la Victoria. Also from that time came the proto-tango "Bartolo tenia una flauta” or simply "Bartolo", derived from a classical XV century Andalusian melody, and the Montevidean “candombe tangueado" "El chicoba”.

The first Andalusian tango to reach mass popularity was composed in Argentina in 1874. The title is "El queco" (slang for ‘brothel’, of Quechua origin), from the Andalusian pianist Heloise de Silva, which makes open reference to the “cuartos de chinas.” Also, a candombe called "tango" titled "El merenguengué" became very successful at carnivals organized by the Afro-Argentinean population in Buenos Aires in February 1876. In 1877, the “Lo de Hansen” restaurant in Palermo was the first in a series of restaurants, cabarets, and pubs where high society youth would socialize and dance Tango.

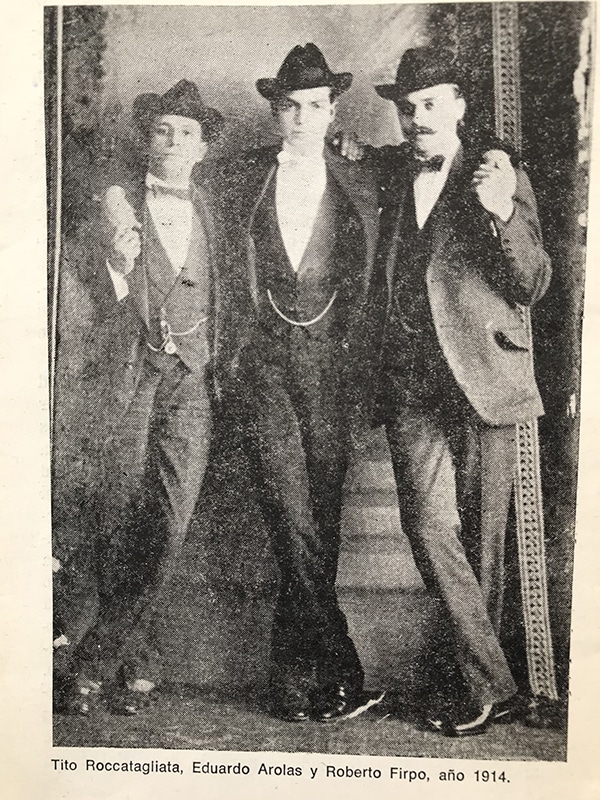

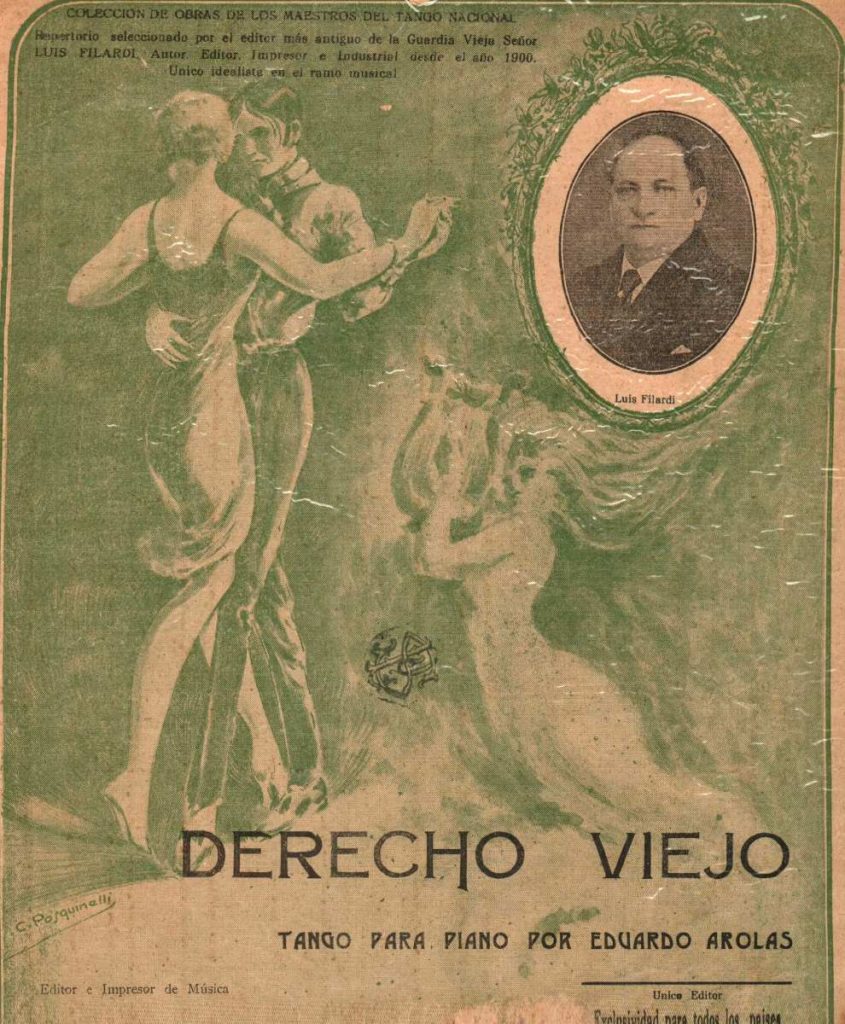

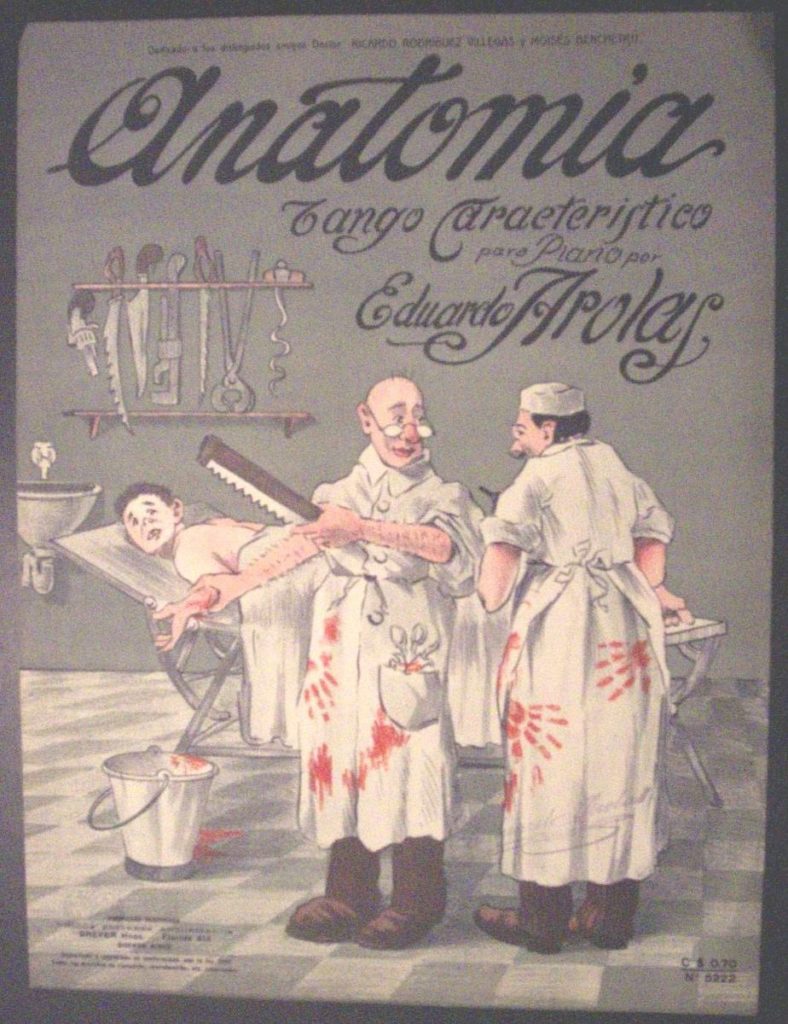

The first Andalusian tango to reach mass popularity was composed in Argentina in 1874. The title is "El queco" (slang for ‘brothel’, of Quechua origin), from the Andalusian pianist Heloise de Silva, which makes open reference to the “cuartos de chinas.” Also, a candombe called "tango" titled "El merenguengué" became very successful at carnivals organized by the Afro-Argentinean population in Buenos Aires in February 1876. In 1877, the “Lo de Hansen” restaurant in Palermo was the first in a series of restaurants, cabarets, and pubs where high society youth would socialize and dance Tango.The year 1880 is when some authors mark the transition between the gestation of the Tango and “La Guardia Vieja” (“Old Guard”.) Some others prefer to wait for the further evolution of the genre and the appearance of the first scores. In this decade, the tango and milonga were confused with one another, and both began to impose their dominance over the habanera. During this time is when tangos began to multiply, “Señora casera" (Anonymous, 1880), “Andate a la Recoleta” (Anonymous, 1880), “Tango # 1” (José Machado, 1883), “Dame la lata” (Juan Pérez, 1883), “Qué polvo con tanto viento” (Pedro M. Quijano, 1890.)

https://escuelatangoba.com/marcelosolis/history-of-tango-part-2/