Considerations on the value of Argentine Tango

I am pleased to share with you some reflections on the value we give to Tango and dancing at the milongas, the place it acquires (or we allow it to acquire) in our lives as milongueros, professionals, teachers, students, etc.

These thoughts took the aphoristic form and different approaches: direct, metaphorical, philosophical, in the form of dialogues with a more or less imaginary or real interlocutor, as a game, and as poetry.

1

You can only dance Tango well if you prioritize it. Many believe that they prioritize dancing Tango, but mostly stay on the edge of it. Proposing to oneself the task of dancing Tango would perhaps imply a profound critique of our way of life, our prejudices concerning what we consider valuable: efficient, productive time, which enriches us in a way that can be "objectively" measured, accounted for through money, through which is appreciated by the most significant number of people and could be counted by the number of "likes" received, by the number of votes obtained, for prizes won, by the number of participants in a class or a milonga, or any event, or the number of tandas danced at a milonga; as opposed to a beautiful time, deep in complex and subtle emotions, subtleties and depths not accessible to all sensibilities, but only to those with enough courage and a taste for adventure, for powerfully transformative discoveries, of which we would perhaps be the only protagonists and witnesses. Of course, it is understandable that for the majority, for whom the subtle and complex is somewhat problematic, the objective amounts and monetary gains are reassuring confirmations of one's beliefs and prejudices.

However, I am encouraged to express my doubts about whether it is possible to dance in general and to dance Tango in particular –considering Tango as the only way we still have to dance fully– without conducting an investigation and a critique of our assumptions and prejudices concerning how we conceive our lives. For example, the bias that what does not produce important economic gains is something of little value.

2

Most feel guilty for enjoying themselves. Considering that what does not imply suffering has no value, or its value is negative, is another prejudice.

The deep joy that Tango produces for those who enjoy it is not, however, the ultimate goal that makes us dance it. Instead, that joy is a by-product. It is the sensation that produces everything that allows us to become stronger and wiser, more sure of ourselves and our originality.

3

In our daily lives, we are always trying to fit more and more actions in the shortest time. This is probably where the habit of trying to put too many steps and embellishments in our dance comes from.

4

An academic studies his subject, and a religious studies his holly book.

The one who dances Tango studies his body, the music, and the culture of Tango and interviews the most expert milongueros in a framework of friendship to investigate the subjective experience of those who danced it long before and dedicated their lives to it.

5

With Tango, it would be demonstrated that the music, to be danceable, does not need to be superficial.

6

Dancing Tango is dancing well, which cannot be achieved by dancing with just anyone. At most, when the person I dance with doesn't allow me to dance well, I can propose to "dance the best possible". In this case, the experience of dancing is degraded; it does not become dancing Tango.

7

The dance is a truth proposition that can always be refuted, contradicted, improved, or partially modified by another dance. Truth here means a way of living, an answer to the question "How to live?"

8

Your dance can present to yourself your way of wanting and living, your ideals, your values as if you were another person who was watching you –something like the impression that seeing yourself in a video for the first time gave you– and if you agree with it if you are proud or ashamed of it, and consequently, if you are proud or ashamed of your life. Then, it would allow you to review your values, change them if you sincerely consider it necessary, or change your feelings concerning your values. It may even allow you to review and restore your honesty about yourself.

9

Learning to live would perhaps be learning to dance with the world. Manage times in a non-mechanical way: with emotion. Don't rush. Don't lose patience. Don't stress. Always be able to move with elasticity, smoothness, and control. Balance in all aspects. Don't run out. Arrive at the end of the day or any activity with an elegant finale.

10

Being a good dancer implies a search for greater balance, control, and ease in your movements, both physically and spiritually. Dancing could lead to a greater awareness of your own body. This would result in a concern to develop increasingly healthy habits and thus develop a more balanced relationship with the people around you and yourself. Dancing could mean getting to know yourself and people in general better. Dancing Tango would then be continually learning to see life from the perspective of a person who dances. Dancing Tango would be something like dancing your life.

11

Everything we incorporate –what we allow to reach us–: food, the people we allow to participate in our lives, what we read, the music we listen to, our acquired habits, etc., constitutes us and would shape everything we do, including our way of dancing.

12

Agility makes spontaneity possible.

13

Just as being happy is not the representation of being happy, dancing Tango is not the representation of dancing Tango.

14

What is dancing well? There are no objective answers that determine it. We can only refer to the emotions that it produces in us.

15

Sense of reality generated thanks to the Tango dance through the inevitability of the body. This is the opposite of virtual reality. However, there are possibilities to be deceived in Tango as well. For example, the memorized steps, focusing on the adjacent of Tango (the sexual, the emotional, the irrational, or the rational, etc.), leaving the actual body – the body that can endure a fight – eclipsed, hidden, postponed, avoided, eliminated.

16

The problem that appears when we do not have internal strength and elasticity is that we tense our external musculature, lose elasticity, take our bone structure towards a fragile rigidity, and become spiritually insecure and vulnerable. Bodily rigidity is also spiritual rigidity.

17

Dancing is a continuous improvement. Dancing –in its most profound sense– would perhaps be becoming the being of becoming, wishing, and acting so that our dance is better, more beautiful, more convincing, and more profound at every moment.

18

About looking at the dance floor. Watching to dance. At first, we see nothing. Being able to dance -knowing how to dance- would increase with that ability to see and understand what happens there. To look, one would also have to know how to be alone. Fear and/or the inability to be alone may not allow us to look. Not looking is not seeing oneself. Because of fear?

19

We may get lost in the infinite surfaces that Tango offers us, and we never explore its depth. When we discover Tango, we discover at the same time that there is something beautiful, deep, mysterious, and exciting in us. However, it could be very easy to stay there, in that initial dazzle, and not encourage ourselves to continue further, towards the interior of Tango itself, and of ourselves, perhaps because we find these two abysses terrifying, these labyrinths in which the most it is likely that we will get lost and never come out again. The truth is that once there, the labyrinth reveals that the essence of our human life is perhaps a labyrinth, an abyss.

20

We should pursue not objective but subjective purposes concerning dance.

We do not dance in the same way. For each of us, dancing means different things. I would say that for me, dancing may be a way of enhancing my humanity.

I would not say that I'm right about dancing Tango (or any dance), only that since we disagree, I prefer not to argue with you about this because, from what I can see in the way you dance, I do not think you have anything to say against my opinion.

However, I would happily share my understanding of what dancing is.

I cannot explain this with words alone because words can't grasp more than a superficial portion of it.

I do not claim here to have any truth, only that I had achieved something regarding my dance which I can claim as successful, something that is not an achievement done and secured, but something that needs to be achieved every day, every time.

I may have a more profound understanding of what dancing means, or perhaps not. You may want to know more about my approach, or you may not care. The only thing we could claim as certain is our dances, every single one of them, at the moment we are dancing.

You may be a profound person. What is happening here is that you are not assigning the dance the depth state I see in it.

Does my approach contradict my joy, smiles, laughter, and lightness while dancing? I argue not. Laughing and dancing are really serious things in human life. Dancing and laughing are where seriousness begins.

You should never ask why someone doesn't dance with you. It is not in good taste. There are no objective reasons. Taste and dance belong to the realm of the subjective.

You could agree with me on words, but more credible would be your agreement manifested in your commitment to your dance.

I do not claim to possess the truth here. Dancing is an absolute stranger to the truth.

I can't convince you. You will agree with me only in what you already agree with yourself.

21

Perhaps most make the moves but still do not dance Tango.

Emotions: the subjectivity in the dance.

The moves: the objective.

Something you can't fake. It is visible in your whole being, your posture, your moves. It is not what you are trying to show through your face.

Some emotions may be in conflict with dancing: anxiety, angriness, fear, shame…

Emotions do not come from yourself alone. Emotions, at least in Tango, which is what concerns us here, have roots not only in yourself but also in your relationships and your position concerning them; that is the milonga as a society, your teacher/s, your students, your peers, the ones you hang out with in the milongas, etc.

It is not the same to be a total stranger in a group, like Tango, as having friends that care about you, teachers that encourage you and help you to be a great dancer –because this is precisely what a good teacher wants from his/her students. I am talking here about the community of Tango as a whole, not in a localized sense, like the Tango community of the Bay Area. If the teacher you take lessons from in Buenos Aires is not at that milonga or local community you are part of, still his/her encouragement and love for Tango shape the emotions of your dance.

Your teacher cares about you as a human being. It is not about you making moves "perfectly". It is about being able to express and explore your humanity.

22

Ultimately, all the subjective approaches to dance would be judged when we all are dancing or not and how, in two, five, ten, or more years.

23

Time plays in my favor. I get to be a better dancer. Does not matter how much I wait to dance with someone I want to dance with.

24

Don't you dance? So you can take on enormous amounts of stress; you can deprive yourself of sleep; you can eat poorly, very poorly... In short, if you're not going to dance, what do your body and health matter to you? What do your spirituality and depth matter to you?

25

In contrast to commercialized art, a humble, honest, and intimate art that spiritualizes and celebrates the body.

Leer este artículo en español

More articles about Argentine Tango

Learn more about Tango

https://escuelatangoba.com/marcelosolis/considerations-on-the-value-of-argentine-tango/

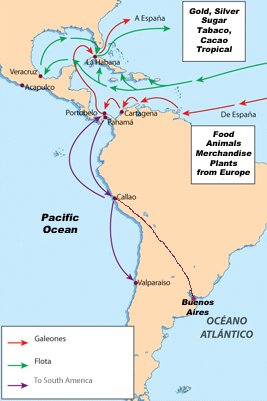

During that time, Spain allowed its colonies to only trade with Spain and other Spanish colonies. To avoid ships being captured by enemy nations and pirates, Spain established a unique route to transit goods between the settlements and Spain. Unfortunately, this route was not favorable to Buenos Aires, making goods too expensive and scarce to the inhabitants of Rio de la Plata. Consequently, smuggling became the only profitable business for its population and the only way to acquire what it needed to survive.

During that time, Spain allowed its colonies to only trade with Spain and other Spanish colonies. To avoid ships being captured by enemy nations and pirates, Spain established a unique route to transit goods between the settlements and Spain. Unfortunately, this route was not favorable to Buenos Aires, making goods too expensive and scarce to the inhabitants of Rio de la Plata. Consequently, smuggling became the only profitable business for its population and the only way to acquire what it needed to survive.

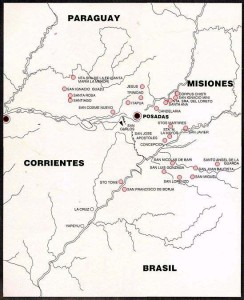

Another origin of gauchos came from the Jesuit Missions after they were dismantled in the area now known as the border between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, populated mainly by natives of the Guaraní nations. These missions were efficiently organized and very productive. For that reason, the missions attracted the attention of the powers of the time, who were suspicious of their prosperity.

Another origin of gauchos came from the Jesuit Missions after they were dismantled in the area now known as the border between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, populated mainly by natives of the Guaraní nations. These missions were efficiently organized and very productive. For that reason, the missions attracted the attention of the powers of the time, who were suspicious of their prosperity. The "facón" was not only a weapon but also an indispensable everyday tool, as well as the "rebenque" and the "poncho".

The "facón" was not only a weapon but also an indispensable everyday tool, as well as the "rebenque" and the "poncho". The gauchos were horseback riders by nature. In their childhoods, they learned to ride horses at the same time; they learned how to walk. Similarly to the cattle that the Spanish brought, the horses brought over from Spain reproduced very quickly, providing the gauchos with a large pool of horses to use and trade. They call their horses "pingo" and "flete."

The gauchos were horseback riders by nature. In their childhoods, they learned to ride horses at the same time; they learned how to walk. Similarly to the cattle that the Spanish brought, the horses brought over from Spain reproduced very quickly, providing the gauchos with a large pool of horses to use and trade. They call their horses "pingo" and "flete." The gaucho’s favorite musical instrument was the guitar (”guitarra criolla”), inherited from Spain (guitarra española.) The poetry of the gauchos accompanied by a guitar is called "payada", and the performer "payador."

The gaucho’s favorite musical instrument was the guitar (”guitarra criolla”), inherited from Spain (guitarra española.) The poetry of the gauchos accompanied by a guitar is called "payada", and the performer "payador."

An example of the ideals of women can be seen in the life of Juana Azurduy de Padilla (1780-1860).

An example of the ideals of women can be seen in the life of Juana Azurduy de Padilla (1780-1860).